A Review of Clinical Pharmacology Considerations in Antibody-drug Conjugates Approved by the US Food and Drug Administration Between 2000 and 2025

by Seoyoung Koo, Chae Yeon Kim, Jeong-hyeon Lim, Eunyoung Lee, In Young Kim, Young G. Shin, and Hanlim Moon

Abstract

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) represent a promising class of anticancer therapies with rapidly expanding development. However, regulatory approval remains complex due to their unique pharmacological properties. We systematically analyzed U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s clinical pharmacology considerations across all approved ADCs to identify consistent regulatory patterns and inform future development strategies. We comprehensively reviewed 13 FDA-approved ADCs as of March 2025, examining clinical pharmacology and/or multidisciplinary reviews from Drugs@FDA. Six key parameters from the FDA’s Clinical Pharmacology Considerations for Antibody-Drug Conjugates: Guidance for Industry (2024) were evaluated: bioanalytical methods, exposure–response relationships, intrinsic factors, extrinsic factors, QTc prolongation, and immunogenicity. For each parameter, we assessed: 1) submission completeness, 2) FDA’s assessment, and 3) whether they led to regulatory actions such as post-marketing requirements/commitments (PMRs/PMCs). All 6 clinical pharmacology considerations were consistently applied throughout ADC approval history, well before the issuance of formal guidance. The FDA maintained particularly rigorous standards across a few critical domains. Exposure—response interpretation considering critical safety issues, intrinsic factor analyses—particularly hepatic impairment and racial variations—and validated immunogenicity assays including the neutralizing antibody emerged as primary scrutiny points. These factors repeatedly triggered similar PMRs/PMCs across multiple ADCs, underscoring their regulatory significance. Core clinical pharmacology parameters consistently shape FDA assessments of ADCs. Proactive alignment with regulatory expectations can streamline development, mitigate potential delays, and reduce post-marketing obligations. Our historical analysis provides strategic insights that may support clinical investigators for optimizing future ADC development.

Introduction

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) have emerged as a transformative class of targeted therapeutics in oncology, combining the selectivity of monoclonal antibodies with the potent cytotoxic activity of chemotherapeutic payloads [1-4]. As of April 2025, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 14 ADCs for various malignancies, and more than 370 candidates have been evaluated in clinical trials worldwide [5,6]. These agents have demonstrated meaningful clinical benefit in both solid tumors and hematologic malignancies, particularly in patients with advanced or refractory disease who otherwise have limited therapeutic options [7].

The regulatory development of ADCs presents unique challenges due to their structural and pharmacological complexity [8]. Each ADC integrates three components—an antibody, a linker, and a cytotoxic payload—yielding pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties that differ from conventional biologics or small molecules and necessitate tailored regulatory assessment [9-11]. Although gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) became the first FDA-approved ADC in 2000 [12]. the Agency only recently issued formal guidance on clinical pharmacology considerations for ADCs. The draft guidance was released in February 2022 and finalized in March 2024, outlining expectations across six key domains: bioanalytical approach, exposure–response (E–R) evaluation, intrinsic factors, drug–drug interactions (DDIs), immunogenicity, and QTc assessment.

While this guidance marks an important milestone, it largely provides broad principles rather than detailed, case-specific directives. Consequently, uncertainties remain among developers regarding which data gaps most often trigger regulatory actions or postmarketing requirements. Furthermore, there has been no comprehensive review of how the FDA has applied these principles in practice across the spectrum of ADC approvals.

To address this gap, we systematically reviewed the FDA’s clinical pharmacology assessments of all approved ADCs. Our objective was to identify consistent regulatory patterns across the six domains, highlight areas of recurrent scrutiny, and provide practical insights for ADC developers and clinical investigators. By mapping historical regulatory experiences, this review aims to guide strategic planning throughout clinical development and ultimately support more efficient, patient-centered ADC development.

SCOPE AND SOURCES OF THE REVIEW

This review encompassed 13 ADCs that had received FDA approval as of April 2025. Although 14 ADCs had been approved in total, moxetumomab pasudotox (Lumoxiti) was excluded because clinical development was discontinued following its voluntary withdrawal. In contrast, belantamab mafodotin (Blenrep) was retained, given its continued clinical investigation and active resubmission process despite market withdrawal after failure in a confirmatory trial [13-15].

Regulatory documentation for each ADC was obtained from the Drugs@FDA database, focusing on the clinical pharmacology review available at the time of initial approval. For gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg), the 2017 re-approval documentation was examined owing to major changes in indication and dosing regimen following its original 2000 approval and subsequent withdrawal [16,17]. When standalone clinical pharmacology reviews were not available—particularly during the FDA’s transition to integrated multidisciplinary reviews between 2015 and 2019 [18]—relevant clinical pharmacology sections of the multidisciplinary review were used. Additional materials, including product labels, summary reviews, and “Other Reviews” documents, were referenced to confirm regulatory context and supplement the extracted information.

The review was organized according to the six domains outlined in the FDA’s Clinical Pharmacology Considerations for Antibody–Drug Conjugates: Guidance for Industry (2024): 1) bioanalytical approach, 2) E–R relationships, 3) intrinsic factors, 4) DDIs, 5) immunogenicity, and 6) QTc assessment. For each domain, we summarize recurring regulatory themes and highlight instances where data limitations or methodological concerns led to postmarketing requirements or commitments (PMRs/PMCs). In this review, PMRs issued solely for confirmatory trials under accelerated approval or those addressing general clinical safety or CMC issues were not considered [19].

KEY FINDINGS FROM FDA REVIEWS OF ADC CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Historical trajectory of approvals

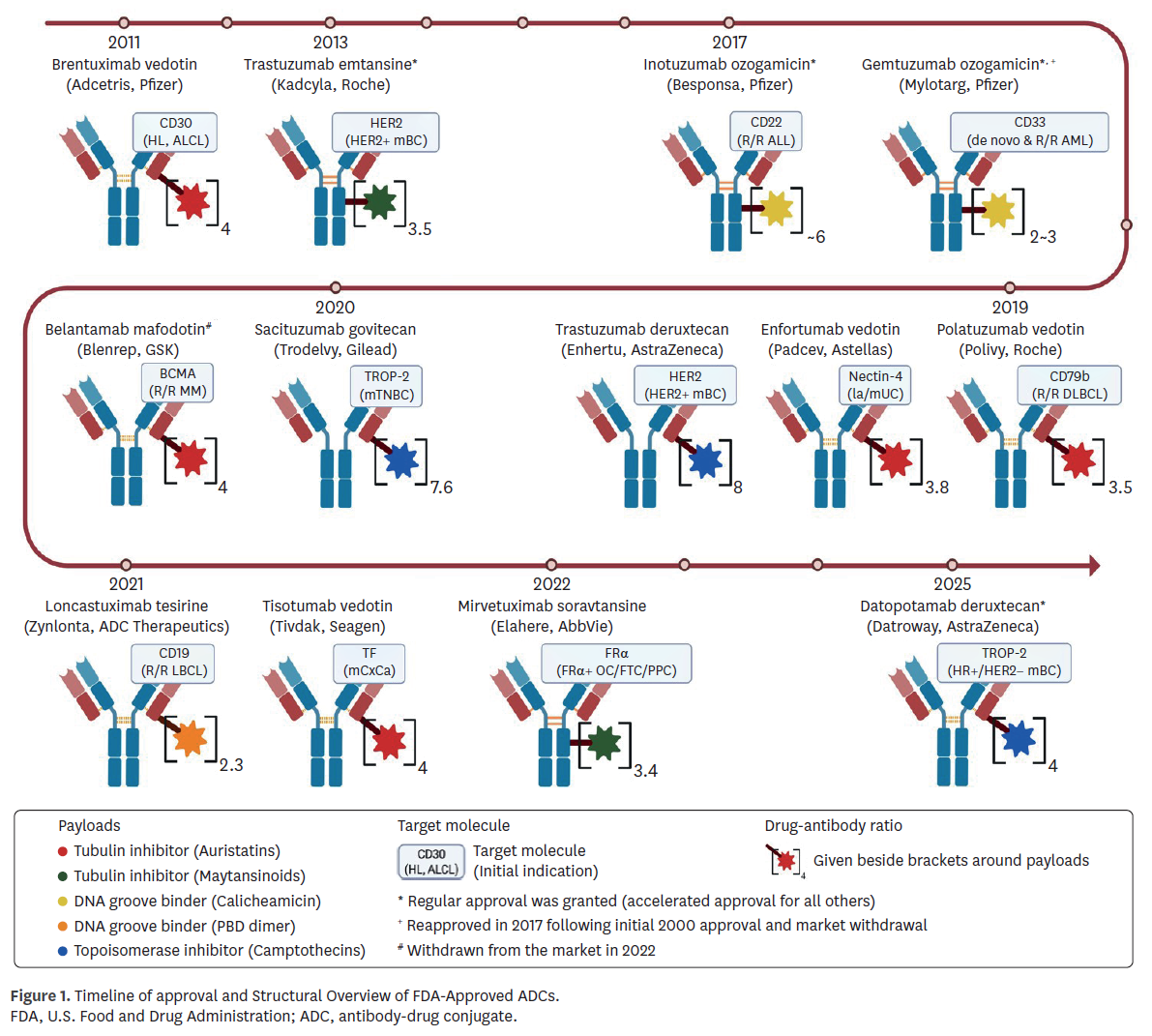

The regulatory history of ADCs began with gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) in 2000, which was later withdrawn in 2010 due to limited benefit and safety concerns, and subsequently reapproved in 2017 following modifications in indication and dosing [20]. Brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris), approved in 2011, therefore represents the longest continuously marketed ADC. As of April 2025, nine of 13 reviewed ADCs (69.2%) received accelerated approval, reflecting the urgency of unmet needs in oncology, while four agents (30.8%) achieved regular approval based on confirmatory data (Fig. 1).

Bioanalytical approaches

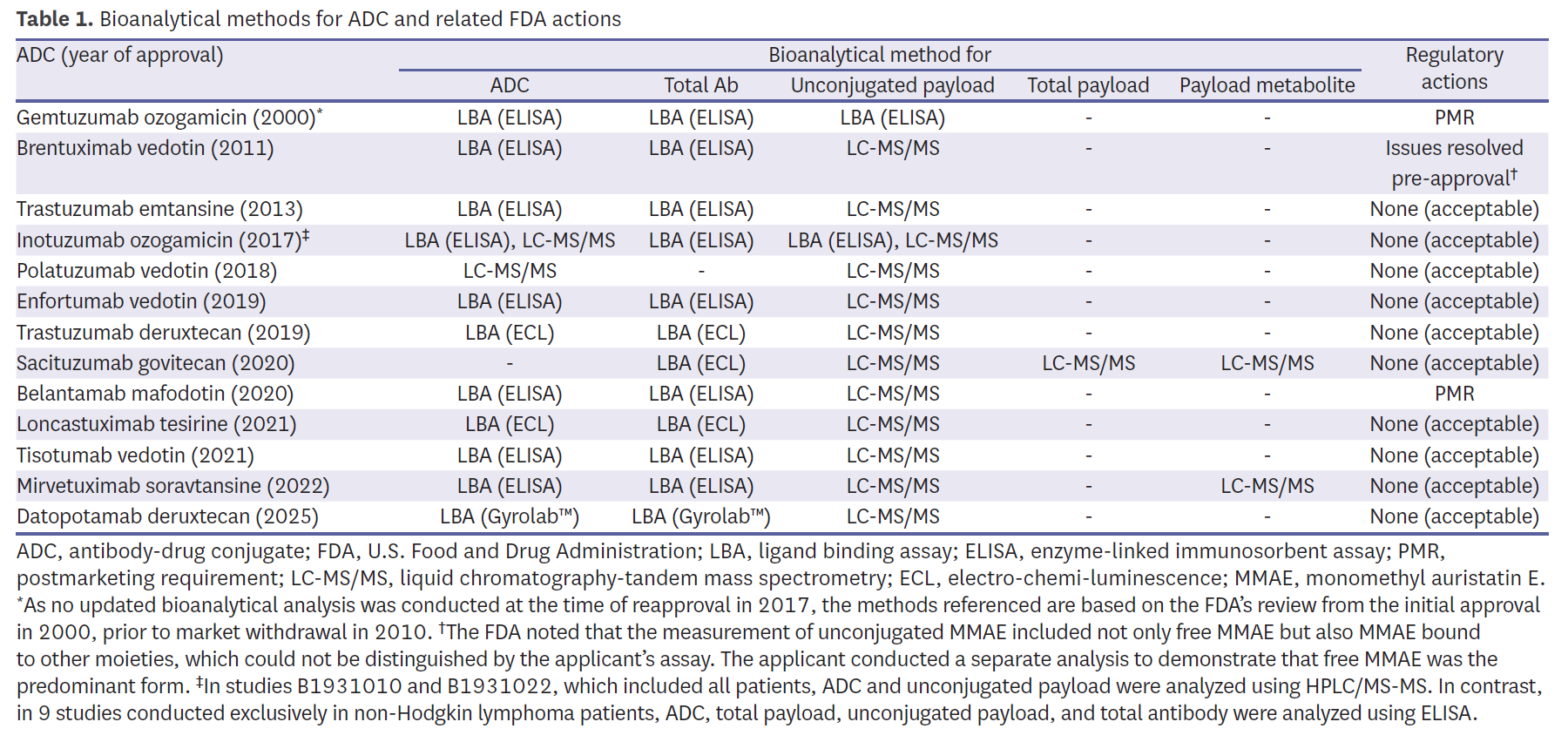

Bioanalytical methods demonstrated broad consistency yet highlighted recurring technical challenges. Most programs quantified intact ADC, total antibody, and unconjugated payload, with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) adopted widely for payload measurement (Table 1). Early programs, such as Mylotarg, relied on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which the FDA later judged insufficient, issuing a PMR for validated assays. Similarly, belantamab mafodotin (Blenrep) was subject to a PMR due to inadequate long-term assay stability. Brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) provided an early example of assay refinement, where unconjugated monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE) measurements initially included both free and bound forms; supplemental analyses were required to demonstrate specificity before approval. More recent programs adopted diversified strategies—for example, sacituzumab govitecan (Trodelvy) estimated intact ADC indirectly using antibody, payload, and metabolite measures—highlighting how bioanalytical flexibility was tolerated when scientifically justified and clinically interpretable. Other recent agents, such as mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere) and datopotamab deruxtecan (Datroway), incorporated metabolite monitoring or novel platforms like Gyrolab™, reflecting a trend toward more robust and high-throughput ligand-binding assays.

E–R relationships

E–R analyses were available for nearly all ADCs (Table 2). For intact ADC, 11 of 12 evaluations (91.7%) demonstrated a positive efficacy relationship. By contrast, analyses for unconjugated payload were inconsistent: some programs reported negative associations with efficacy, while others lacked sufficient systemic concentrations for meaningful modeling. For safety, E–R analyses for intact ADC showed a consistent positive relationship across 12 programs (92.3%). For example, inotuzumab ozogamicin (Besponsa) exhibited a clear link between exposure and efficacy but also a strong association with hepatic veno-occlusive disease (VOD), leading to a PMR for dose-finding studies. Trastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla) demonstrated positive survival relationships but required a PMC for further analyses due to methodological concerns. More recent ADCs such as trastuzumab deruxtecan (Enhertu) provided detailed modeling that linked higher exposure to both efficacy and interstitial lung disease, underscoring the value of robust exposure–toxicity assessments. Collectively, these findings underscore that FDA relied primarily on intact-ADC exposure for dose justification, while payload analyses often faced technical or biological limitations.

Intrinsic factors

Consideration of intrinsic factors frequently exposed gaps. Three ADCs—loncastuximab tesirine (Zynlonta), mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere), and datopotamab deruxtecan (Datroway)—were criticized for underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minorities, leading to PMRs (Table 3). Body weight was identified as a significant covariate in 5 ADCs, but explicit dose capping was applied in only 2 (Padcev and Datroway). Furthermore, insufficient data in hepatic or renal impairment prompted additional PMRs/PMCs for five ADCs (38.5%). For instance, sacituzumab govitecan (Trodelvy) was subject to a PMR to evaluate safety in UGT1A1*28 homozygous patients, reflecting concerns about pharmacogenomic variability. Trastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla) and belantamab mafodotin (Blenrep) were both required to generate further data in patients with hepatic impairment, while renal impairment remained less thoroughly assessed across the class. These patterns emphasize the FDA’s increasing expectation for representative demographics and robust covariate analyses to ensure safe dosing across patient subgroups.