A Review of Clinical Pharmacology Considerations in Antibody-drug Conjugates Approved by the US Food and Drug Administration Between 2000 and 2025

by Seoyoung Koo, Chae Yeon Kim, Jeong-hyeon Lim, Eunyoung Lee, In Young Kim, Young G. Shin, and Hanlim Moon

Abstract

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) represent a promising class of anticancer therapies with rapidly expanding development. However, regulatory approval remains complex due to their unique pharmacological properties. We systematically analyzed U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s clinical pharmacology considerations across all approved ADCs to identify consistent regulatory patterns and inform future development strategies. We comprehensively reviewed 13 FDA-approved ADCs as of March 2025, examining clinical pharmacology and/or multidisciplinary reviews from Drugs@FDA. Six key parameters from the FDA’s Clinical Pharmacology Considerations for Antibody-Drug Conjugates: Guidance for Industry (2024) were evaluated: bioanalytical methods, exposure–response relationships, intrinsic factors, extrinsic factors, QTc prolongation, and immunogenicity. For each parameter, we assessed: 1) submission completeness, 2) FDA’s assessment, and 3) whether they led to regulatory actions such as post-marketing requirements/commitments (PMRs/PMCs). All 6 clinical pharmacology considerations were consistently applied throughout ADC approval history, well before the issuance of formal guidance. The FDA maintained particularly rigorous standards across a few critical domains. Exposure—response interpretation considering critical safety issues, intrinsic factor analyses—particularly hepatic impairment and racial variations—and validated immunogenicity assays including the neutralizing antibody emerged as primary scrutiny points. These factors repeatedly triggered similar PMRs/PMCs across multiple ADCs, underscoring their regulatory significance. Core clinical pharmacology parameters consistently shape FDA assessments of ADCs. Proactive alignment with regulatory expectations can streamline development, mitigate potential delays, and reduce post-marketing obligations. Our historical analysis provides strategic insights that may support clinical investigators for optimizing future ADC development.

Introduction

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) have emerged as a transformative class of targeted therapeutics in oncology, combining the selectivity of monoclonal antibodies with the potent cytotoxic activity of chemotherapeutic payloads [1-4]. As of April 2025, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 14 ADCs for various malignancies, and more than 370 candidates have been evaluated in clinical trials worldwide [5,6]. These agents have demonstrated meaningful clinical benefit in both solid tumors and hematologic malignancies, particularly in patients with advanced or refractory disease who otherwise have limited therapeutic options [7].

The regulatory development of ADCs presents unique challenges due to their structural and pharmacological complexity [8]. Each ADC integrates three components—an antibody, a linker, and a cytotoxic payload—yielding pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties that differ from conventional biologics or small molecules and necessitate tailored regulatory assessment [9-11]. Although gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) became the first FDA-approved ADC in 2000 [12]. the Agency only recently issued formal guidance on clinical pharmacology considerations for ADCs. The draft guidance was released in February 2022 and finalized in March 2024, outlining expectations across six key domains: bioanalytical approach, exposure–response (E–R) evaluation, intrinsic factors, drug–drug interactions (DDIs), immunogenicity, and QTc assessment.

While this guidance marks an important milestone, it largely provides broad principles rather than detailed, case-specific directives. Consequently, uncertainties remain among developers regarding which data gaps most often trigger regulatory actions or postmarketing requirements. Furthermore, there has been no comprehensive review of how the FDA has applied these principles in practice across the spectrum of ADC approvals.

To address this gap, we systematically reviewed the FDA’s clinical pharmacology assessments of all approved ADCs. Our objective was to identify consistent regulatory patterns across the six domains, highlight areas of recurrent scrutiny, and provide practical insights for ADC developers and clinical investigators. By mapping historical regulatory experiences, this review aims to guide strategic planning throughout clinical development and ultimately support more efficient, patient-centered ADC development.

SCOPE AND SOURCES OF THE REVIEW

This review encompassed 13 ADCs that had received FDA approval as of April 2025. Although 14 ADCs had been approved in total, moxetumomab pasudotox (Lumoxiti) was excluded because clinical development was discontinued following its voluntary withdrawal. In contrast, belantamab mafodotin (Blenrep) was retained, given its continued clinical investigation and active resubmission process despite market withdrawal after failure in a confirmatory trial [13-15].

Regulatory documentation for each ADC was obtained from the Drugs@FDA database, focusing on the clinical pharmacology review available at the time of initial approval. For gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg), the 2017 re-approval documentation was examined owing to major changes in indication and dosing regimen following its original 2000 approval and subsequent withdrawal [16,17]. When standalone clinical pharmacology reviews were not available—particularly during the FDA’s transition to integrated multidisciplinary reviews between 2015 and 2019 [18]—relevant clinical pharmacology sections of the multidisciplinary review were used. Additional materials, including product labels, summary reviews, and “Other Reviews” documents, were referenced to confirm regulatory context and supplement the extracted information.

The review was organized according to the six domains outlined in the FDA’s Clinical Pharmacology Considerations for Antibody–Drug Conjugates: Guidance for Industry (2024): 1) bioanalytical approach, 2) E–R relationships, 3) intrinsic factors, 4) DDIs, 5) immunogenicity, and 6) QTc assessment. For each domain, we summarize recurring regulatory themes and highlight instances where data limitations or methodological concerns led to postmarketing requirements or commitments (PMRs/PMCs). In this review, PMRs issued solely for confirmatory trials under accelerated approval or those addressing general clinical safety or CMC issues were not considered [19].

KEY FINDINGS FROM FDA REVIEWS OF ADC CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Historical trajectory of approvals

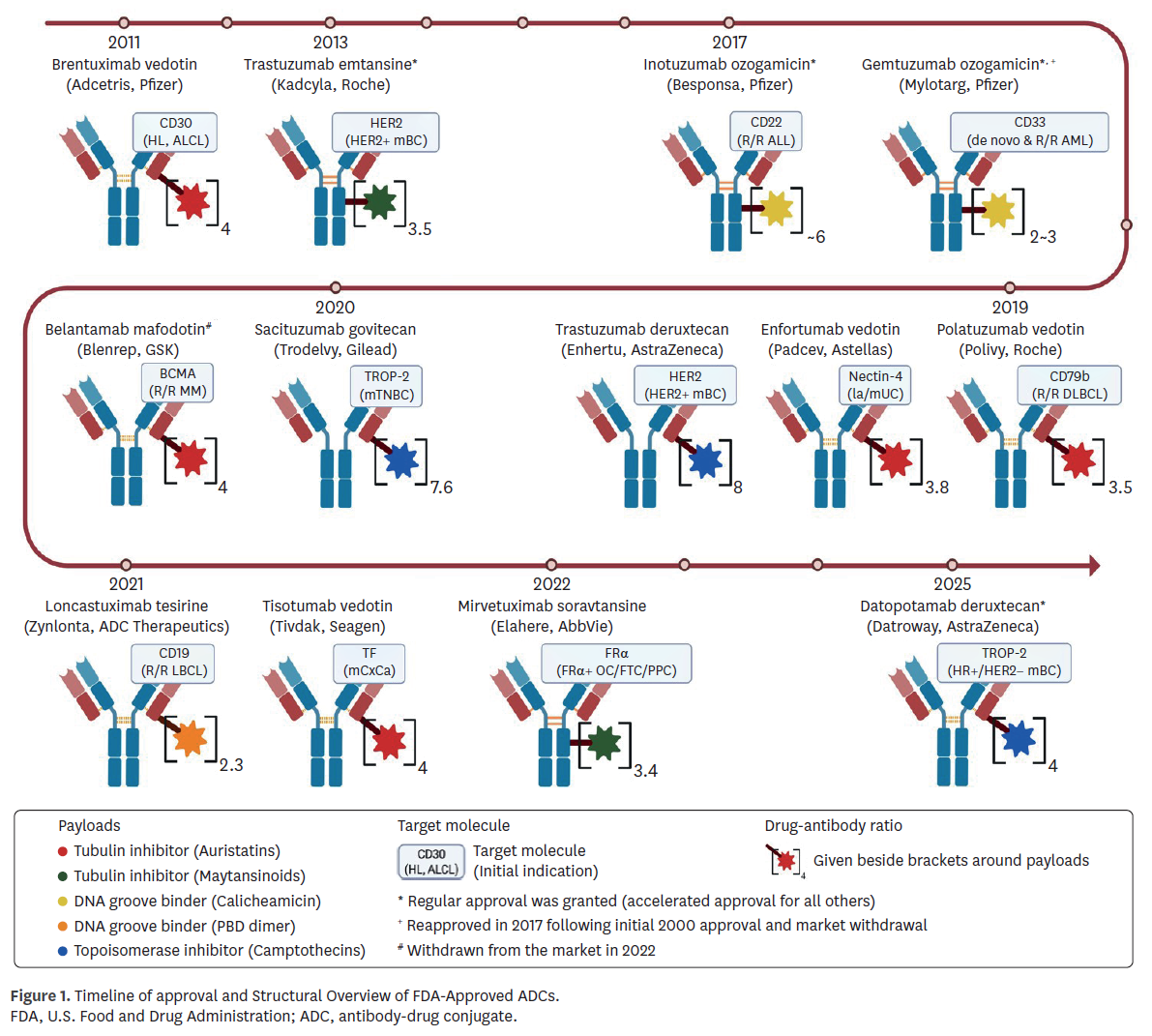

The regulatory history of ADCs began with gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) in 2000, which was later withdrawn in 2010 due to limited benefit and safety concerns, and subsequently reapproved in 2017 following modifications in indication and dosing [20]. Brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris), approved in 2011, therefore represents the longest continuously marketed ADC. As of April 2025, nine of 13 reviewed ADCs (69.2%) received accelerated approval, reflecting the urgency of unmet needs in oncology, while four agents (30.8%) achieved regular approval based on confirmatory data (Fig. 1).

Bioanalytical approaches

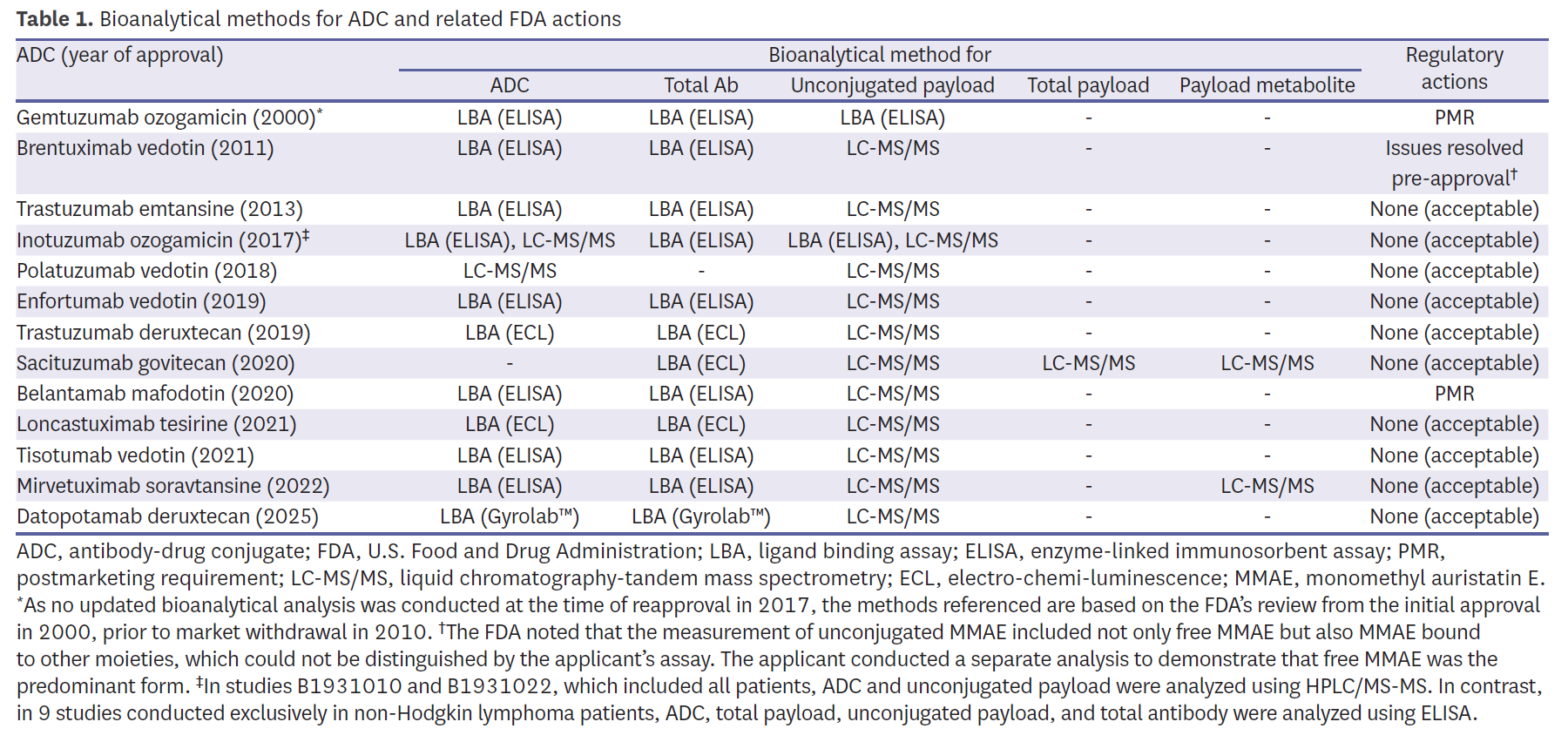

Bioanalytical methods demonstrated broad consistency yet highlighted recurring technical challenges. Most programs quantified intact ADC, total antibody, and unconjugated payload, with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) adopted widely for payload measurement (Table 1). Early programs, such as Mylotarg, relied on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which the FDA later judged insufficient, issuing a PMR for validated assays. Similarly, belantamab mafodotin (Blenrep) was subject to a PMR due to inadequate long-term assay stability. Brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) provided an early example of assay refinement, where unconjugated monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE) measurements initially included both free and bound forms; supplemental analyses were required to demonstrate specificity before approval. More recent programs adopted diversified strategies—for example, sacituzumab govitecan (Trodelvy) estimated intact ADC indirectly using antibody, payload, and metabolite measures—highlighting how bioanalytical flexibility was tolerated when scientifically justified and clinically interpretable. Other recent agents, such as mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere) and datopotamab deruxtecan (Datroway), incorporated metabolite monitoring or novel platforms like Gyrolab™, reflecting a trend toward more robust and high-throughput ligand-binding assays.

E–R relationships

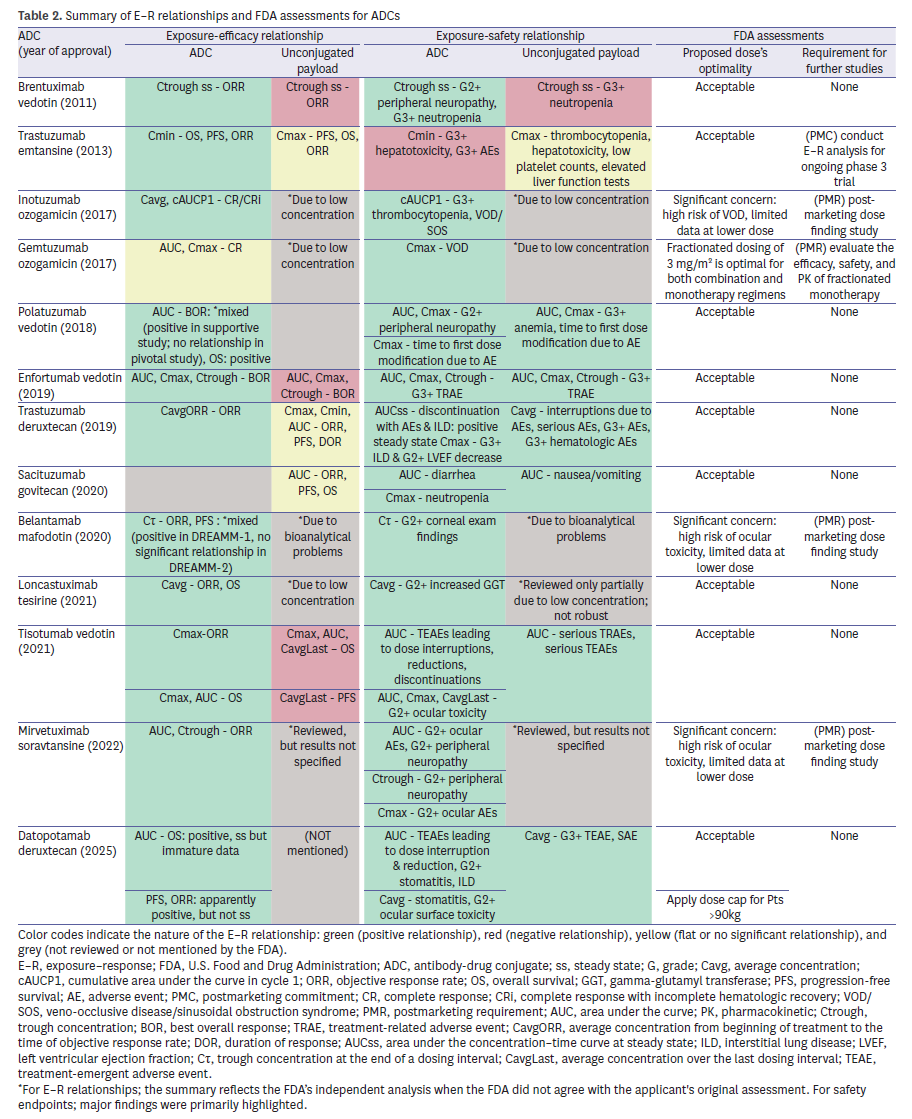

E–R analyses were available for nearly all ADCs (Table 2). For intact ADC, 11 of 12 evaluations (91.7%) demonstrated a positive efficacy relationship. By contrast, analyses for unconjugated payload were inconsistent: some programs reported negative associations with efficacy, while others lacked sufficient systemic concentrations for meaningful modeling. For safety, E–R analyses for intact ADC showed a consistent positive relationship across 12 programs (92.3%). For example, inotuzumab ozogamicin (Besponsa) exhibited a clear link between exposure and efficacy but also a strong association with hepatic veno-occlusive disease (VOD), leading to a PMR for dose-finding studies. Trastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla) demonstrated positive survival relationships but required a PMC for further analyses due to methodological concerns. More recent ADCs such as trastuzumab deruxtecan (Enhertu) provided detailed modeling that linked higher exposure to both efficacy and interstitial lung disease, underscoring the value of robust exposure–toxicity assessments. Collectively, these findings underscore that FDA relied primarily on intact-ADC exposure for dose justification, while payload analyses often faced technical or biological limitations.

Intrinsic factors

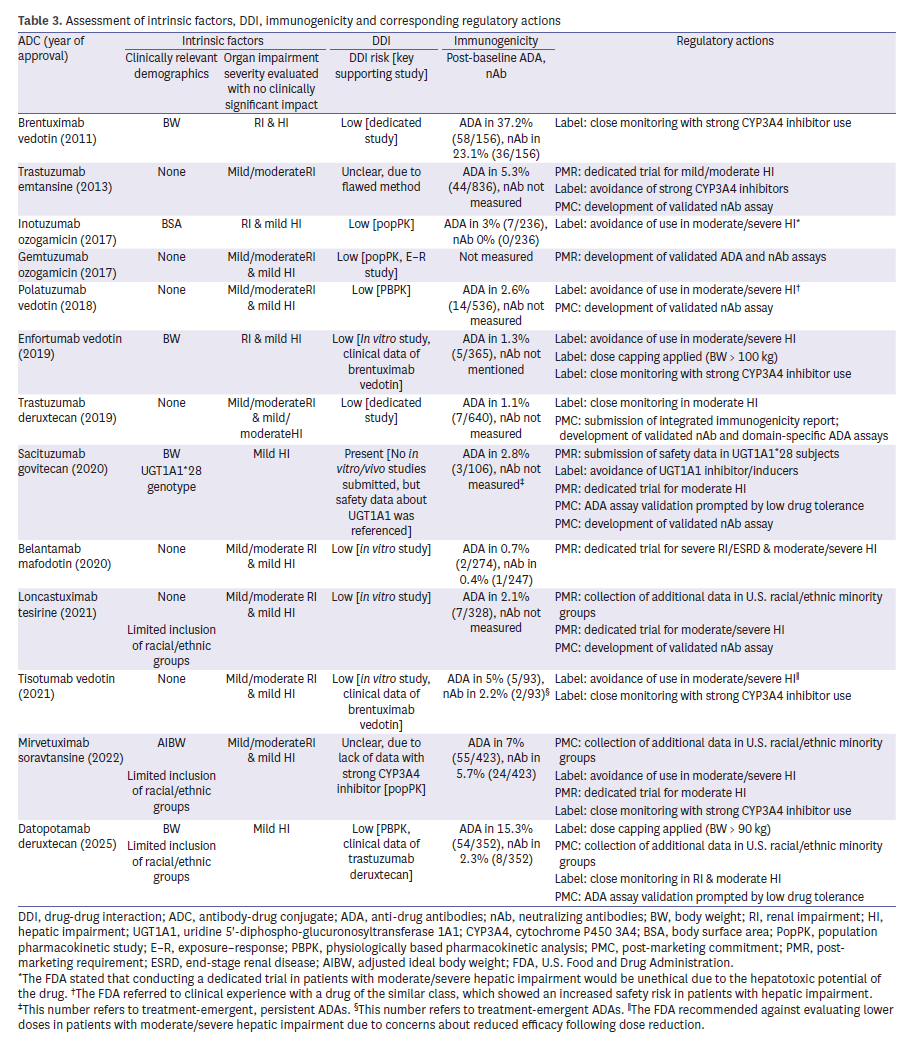

Consideration of intrinsic factors frequently exposed gaps. Three ADCs—loncastuximab tesirine (Zynlonta), mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere), and datopotamab deruxtecan (Datroway)—were criticized for underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minorities, leading to PMRs (Table 3). Body weight was identified as a significant covariate in 5 ADCs, but explicit dose capping was applied in only 2 (Padcev and Datroway). Furthermore, insufficient data in hepatic or renal impairment prompted additional PMRs/PMCs for five ADCs (38.5%). For instance, sacituzumab govitecan (Trodelvy) was subject to a PMR to evaluate safety in UGT1A1*28 homozygous patients, reflecting concerns about pharmacogenomic variability. Trastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla) and belantamab mafodotin (Blenrep) were both required to generate further data in patients with hepatic impairment, while renal impairment remained less thoroughly assessed across the class. These patterns emphasize the FDA’s increasing expectation for representative demographics and robust covariate analyses to ensure safe dosing across patient subgroups.

DDIs

All ADCs were assessed for potential DDIs, though evidentiary approaches varied: 2 relied on dedicated clinical trials, 2 used physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling, and three applied population PK analyses (Table 3). FDA sometimes accepted cross-program extrapolation, such as using Adcetris data to support Padcev and Tivdak. In other cases, the Agency requested further validation when mechanistic concerns remained unresolved. For instance, sacituzumab govitecan (Trodelvy) was required to provide additional safety data in patients with UGT1A1*28 variants, reflecting concern over metabolic interactions with irinotecan’s active metabolite. Similarly, for polatuzumab vedotin (Polivy), in vitro results suggested limited cytochrome P450 involvement, but the FDA still imposed labeling restrictions regarding use in patients with moderate to severe hepatic impairment, indirectly linked to DDI risk. These experiences highlight both the Agency’s pragmatic acceptance of scientifically justified extrapolation and its insistence on clear mechanistic rationale for transporter or enzyme interactions.

Immunogenicity

Assessment of anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) was nearly universal (12 of 13 ADCs, 92.3%), but neutralizing antibody (nAb) testing was less common (6 of 13, 46.2%) (Table 3). In all cases where nAb testing was omitted, the FDA mandated PMRs, underscoring the perceived importance of functional immunogenicity. Low drug tolerance in ADA assays further led to PMCs for assay validation in Trodelvy and Datroway. Even agents with low observed ADA incidence, such as trastuzumab deruxtecan (Enhertu), were still required to submit integrated immunogenicity summaries, reflecting the Agency’s precautionary stance. Overall, these findings demonstrate FDA’s insistence on robust and validated immunogenicity assessments, even when clinical incidence appears low.

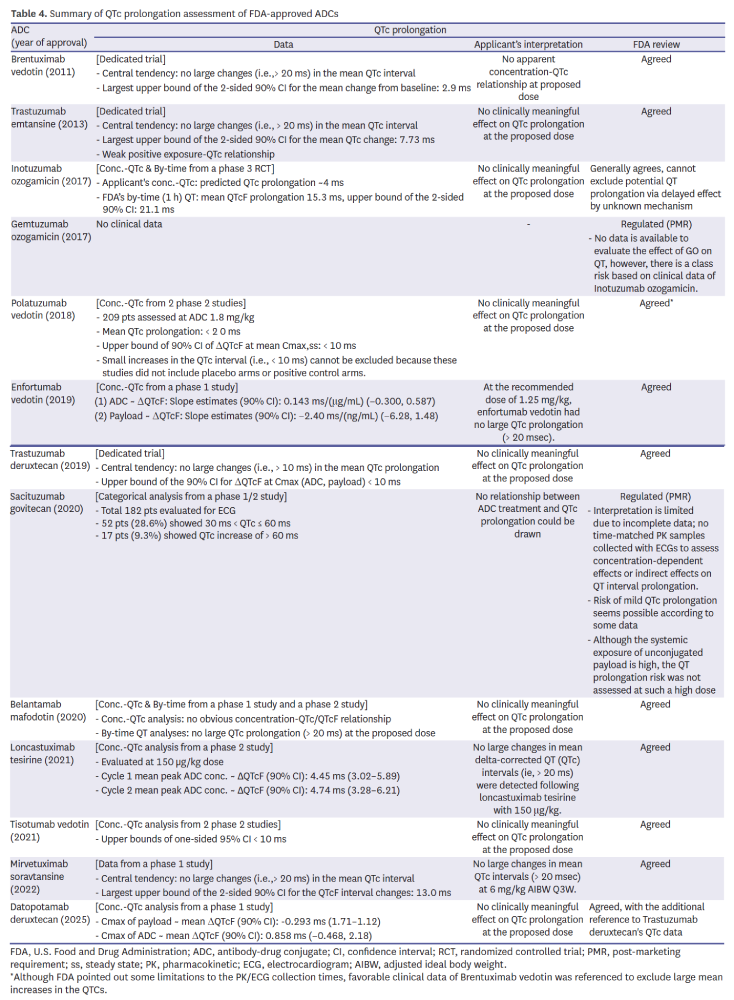

QTc assessment

Evaluation of cardiac repolarization risk relied on a mix of dedicated QTc trials (e.g., Adcetris, Kadcyla, Enhertu) and concentration–QTc modeling in later programs (Table 4). Despite the growing reliance on modeling, Mylotarg and Trodelvy still received PMRs due to inadequate data. For example, reliance on early-phase concentration–QTc modeling needed supportive clinical context, as shown by datopotamab deruxtecan where reference was made to trastuzumab deruxtecan’s safety profile. This highlights FDA’s willingness to accept innovative approaches while retaining conservative standards when data completeness is in question.

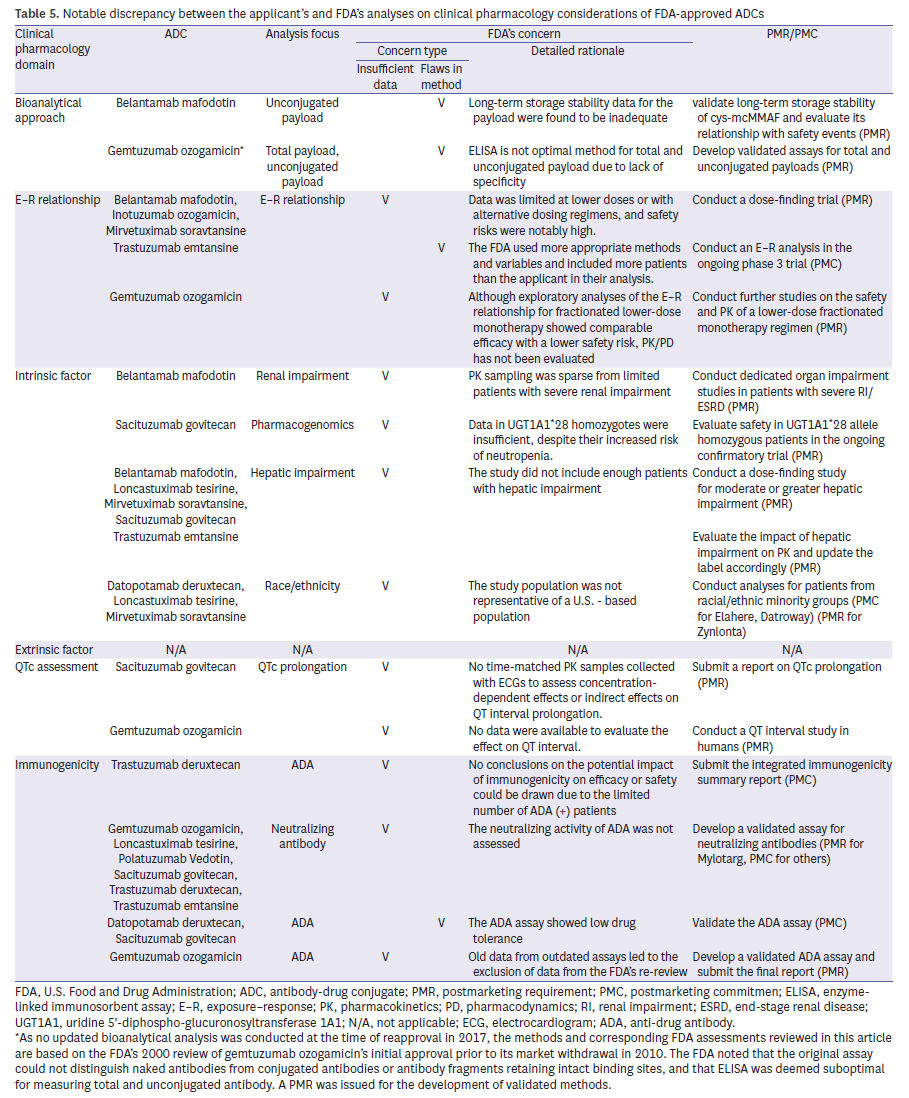

Regulatory actions (PMRs and PMCs)

Across the six domains, recurrent deficiencies consistently led to regulatory actions (Table 5). Immunogenicity gaps, intrinsic factor underrepresentation, and insufficient E–R evaluation were the most common triggers. PMRs requiring dose-finding studies were issued for Blenrep, Besponsa, and Elahere due to safety concerns and inadequate dose exploration. Additional studies in hepatic impairment were mandated for 5 ADCs, and demographic diversity requirements were applied to three recent programs. In immunogenicity, absent nAb assays or suboptimal ADA assay validation were near-universal drivers of regulatory actions. These trends illustrate that FDA’s scrutiny focuses less on novelty per se and more on data sufficiency in recurring, well-defined domains.

Examples illustrate how these patterns played out. Inotuzumab ozogamicin (Besponsa) received a PMR for postmarketing dose-finding because of high VOD risk and limited low-dose data, while Blenrep and Elahere were subject to similar requirements due to ocular toxicity. Hepatic impairment was another recurring issue, with Kadcyla, Trodelvy, and Blenrep all required to provide additional data given sparse PK sampling. More recent approvals, such as Zynlonta and Datroway, faced obligations to address underrepresentation of U.S. racial and ethnic minorities. Finally, gaps in immunogenicity were common, with multiple ADCs asked to develop validated nAb assays or improve ADA assay drug tolerance.

Together, these trends show that FDA’s focus was not on novelty itself but on recurring domains where insufficient data undermined confidence. Addressing these areas proactively may reduce the likelihood of burdensome PMRs or PMCs.

DISCUSSION AND LESSONS LEARNED

The regulatory assessment of ADCs highlights the unique intersection of structural complexity, translational pharmacology, and oncology drug development [21]. Clinical pharmacology has consistently shaped the FDA’s evaluation, not only guiding initial approval but also prompting a significant proportion of postmarketing requirements and commitments (PMRs/PMCs) [22]. From our analysis of 13 FDA-approved ADCs, three recurrent regulatory themes emerged: i) the FDA’s reliance on independent analyses beyond sponsor submissions, ii) regulatory flexibility balanced by an uncompromising focus on safety, and iii) evolving priorities reflecting demographic diversity and individualized dosing.

Independent analyses beyond sponsor submissions

FDA reviews often extended beyond sponsor-generated analyses, re-examining E–R relationships and DDI risks with alternative models and endpoints. A notable example is trastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla), where the Agency rejected the sponsor’s pooling of drug classes in DDI assessment and instead conducted its own population pharmacokinetic (popPK) modeling. Similarly, while the sponsor reported no significant E–R for efficacy using area under the curve, FDA applied trough concentrations and broader datasets to identify a meaningful positive relationship. These practices underscore the Agency’s proactive stance in independently interrogating sponsor data, particularly when methodologies are incomplete or suboptimal [22].

Analyte selection and evolution of bioanalytical methods

A notable area in which FDA scrutiny has been consistent across programs is the selection of analytes and the evolution of bioanalytical methodologies supporting ADC development. Early ADCs such as gemtuzumab ozogamicin relied primarily on ELISA-based assays, which lacked the specificity to distinguish intact conjugates from partially deconjugated species, leading to PMRs requesting validated methods. As linker technologies and payload diversity expanded, sponsors increasingly adopted LC-MS/MS for unconjugated payloads and incorporated metabolite monitoring when relevant, as seen with mirvetuximab soravtansine. These trends reflect a broader regulatory expectation that analyte selection be scientifically justified based on ADC structure, linker stability, and payload behavior. The FDA’s emphasis on analyte appropriateness demonstrates that inadequate or non-specific bioanalytical approaches can undermine E–R interpretation and ultimately affect regulatory confidence in dose justification.

Flexibility with clear boundaries on safety

Although FDA accepted alternative scientific approaches under certain conditions, safety considerations consistently delineated non-negotiable boundaries. For instance, sacituzumab govitecan (Trodelvy) did not quantify intact ADC directly, instead inferring exposure through antibody, payload, and metabolite levels. This strategy was tolerated, likely because the payload SN-38 has a well-established safety profile from decades of irinotecan use [23,24]. Similarly, negative or inconsistent E–R findings for unconjugated payloads in multiple ADCs did not automatically trigger additional studies, as the Agency recognized biological explanations and limited clinical relevance. By contrast, when safety risks were evident—hepatic VOD with inotuzumab ozogamicin (Besponsa) or ocular toxicity with belantamab mafodotin (Blenrep) and mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere)—PMRs mandating dose-finding trials were issued. These examples illustrate how regulatory flexibility was applied to efficacy uncertainties but curtailed when safety signals emerged.

Mechanistic interpretation of divergent E–R patterns

A key pattern is that intact-ADC exposure often correlates with efficacy, while unconjugated payload frequently does not. This divergence aligns with ADC design principles: stable linkers, tumor-targeted delivery, and intracellular payload release mean that plasma payload levels are not reliable markers of tumor drug exposure. For example, mirvetuximab soravtansine showed clear intact-ADC E–R for efficacy but no meaningful payload E–R because its DM4 payload is rapidly converted intracellularly, limiting systemic detection.

Conversely, several MMAE-based ADCs (e.g., brentuximab vedotin) demonstrated negative payload–efficacy relationships, indicating that higher circulating payload may represent off-target exposure contributing to toxicity rather than benefit. These cases illustrate how payload E–R signals may reflect systemic burden rather than tumor delivery, reinforcing the limited utility of plasma payload measurements for dose justification.

Clinically, these mechanistic mismatches can complicate dose optimization. For instance, inotuzumab ozogamicin showed strong exposure–toxicity associations (VOD) but limited dose-level exploration, prompting an FDA PMR despite reasonable efficacy. This demonstrates how inconclusive or contradictory E–R relationships can directly lead to regulatory actions when safety margins are unclear.

Moving forward, mechanistic PK/PD modeling, tumor payload quantification, and linker-stability characterization may better contextualize E–R findings and reduce reliance on plasma measurements that insufficiently capture ADC pharmacology. These strategies could strengthen dose justification and help avoid PMRs related to inadequate E–R characterization.

Interpreting immunogenicity evidence in ADC development

Immunogenicity remains a recurring area of regulatory scrutiny, not only because ADA or nAb formation can alter exposure but also because current nonclinical models have limited ability to predict clinical risk. Preclinical assays—including in vitro T-cell activation or animal ADA evaluations—provide early signals but do not reliably translate to human responses due to species differences and the hybrid biologic–small molecule structure of ADCs. Across FDA reviews, adequacy of immunogenicity evidence depended largely on assay drug tolerance, sufficient sampling duration, and the ability to interpret PK or safety trends among ADA-positive subjects. Cases such as trastuzumab deruxtecan or sacituzumab govitecan demonstrate that even low ADA incidence does not exempt sponsors from providing validated nAb assays, as uncertainty in immunogenicity directly influences confidence in exposure, safety margins, and labeling decisions. These observations suggest that future ADC programs may need more robust, mechanism-informed immunogenicity strategies to reduce postmarketing obligations.

Increasing attention to demographic diversity and individualization

Recent approvals reflect a shift toward regulatory emphasis on underrepresented populations and precision dosing strategies. PMRs requiring enrollment of racial and ethnic minorities were issued for loncastuximab tesirine (Zynlonta), mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere), and datopotamab deruxtecan (Datroway). Similarly, body weight, identified as a key pharmacokinetic covariate in several ADCs, was operationalized into dose caps for Padcev and Datroway. These requirements signal FDA’s heightened expectation that pivotal trials reflect real-world U.S. demographics and that dosing strategies account for interpatient variability. Such priorities mirror broader regulatory trends in oncology toward equity and individualized therapy. They also highlight the practical need for sponsors to design global trials with foresight, ensuring that enrollment plans and PK analyses can withstand scrutiny at the time of regulatory review.

Implications for future ADC development

Recurring regulatory actions highlight specific domains where sponsors frequently encounter deficiencies: E–R modeling, hepatic impairment evaluation, demographic representation, and immunogenicity assay validation. Proactive attention to these areas during development could reduce regulatory uncertainty, mitigate operational delays, and decrease the burden of postmarketing studies. In particular, lessons from past approvals suggest that reliance on limited E–R data or sparse PK sampling is often deemed inadequate by the FDA, leading to requests for additional trials or expanded datasets. For developers, early integration of popPKs, dedicated hepatic impairment cohorts, validated nAb assays, and deliberate enrollment strategies for minority populations represent actionable strategies. Such proactive measures not only align with regulatory expectations but also strengthen confidence in labeling, ultimately improving clinical uptake and patient access to new ADCs.

Looking ahead, next-generation ADC platforms—including bispecific or biparatopic antibodies, site-specific conjugation technologies, dual-payload constructs, and rational combinations with immune checkpoint inhibitors or targeted agents—are likely to amplify clinical pharmacology challenges. For these modalities, issues such as target co-expression, non-linear target-mediated disposition, overlapping toxicities between payloads and partner therapies, and complex immunogenicity profiles will require even more integrated translational and quantitative approaches than those applied to first-generation ADCs.

Limitations of the review

This analysis is based solely on publicly available FDA review documents, which, while comprehensive, do not capture confidential sponsor–Agency communications. As regulatory science evolves, earlier approvals may not fully reflect current standards. To minimize temporal bias, ADCs were considered chronologically, allowing insights into shifting expectations. Finally, although abstraction was conducted by multiple reviewers and adjudicated by a broader panel, interpretive bias inherent in qualitative synthesis cannot be completely excluded. In addition, our review did not examine regulatory assessments from other agencies such as EMA or PMDA, which may apply distinct standards, limiting the generalizability of our findings outside the U.S. context. Furthermore, as this was a qualitative synthesis rather than a quantitative meta-analysis, conclusions should be interpreted as reflective of regulatory trends rather than absolute effect estimates.

Key insights

Overall, the regulatory experience with ADCs demonstrates that:

- FDA independently interrogates sponsor submissions, frequently redefining conclusions in favor of methodological rigor.

- Regulatory flexibility is conditional, with safety-related uncertainties consistently triggering PMRs/PMCs.

- Demographic diversity and precision dosing are emerging priorities, shaping regulatory expectations for newer ADCs.

By addressing these recurring domains early, developers may not only expedite regulatory approval but also ensure broader and safer patient access to these complex therapeutics.

REFERENCES

1. Boni V, Sharma MR, Patnaik A. The resurgence of antibody drug conjugates in cancer therapeutics: novel targets and payloads. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2020;40:1-17.

2. Parit S, Manchare A, Gholap AD, Mundhe P, Hatvate N, Rojekar S, et al. Antibody-drug conjugates: a promising breakthrough in cancer therapy. Int J Pharm 2024;659:124211.

3. Jaime-Casas S, Barragan-Carrillo R, Tripathi A. Antibody-drug conjugates in solid tumors: a new frontier. Curr Opin Oncol 2024;36:421-429.

4. Fu Z, Li S, Han S, Shi C, Zhang Y. Antibody drug conjugate: the “biological missile” for targeted cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022;7:93.

5. Colombo R, Tarantino P, Rich JR, LoRusso PM, de Vries EGE. The journey of antibody–drug conjugates: lessons learned from 40 years of development. Cancer Discov 2024;14:2089-2108.

6. Riccardi F, Dal Bo M, Macor P, Toffoli G. A comprehensive overview on antibody-drug conjugates: from the conceptualization to cancer therapy. Front Pharmacol 2023;14:1274088.

7. Wang R, Hu B, Pan Z, Mo C, Zhao X, Liu G, et al. Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs): current and future biopharmaceuticals. J Hematol Oncol 2025;18:51.

8. Wen L, Zhang Y, Sun C, Wang SS, Gong Y, Jia C, et al. Fundamental properties and principal areas of focus in antibody-drug conjugates formulation development. Antib Ther 2025;8:99-110.

9. Tarantino P, Pestana RC, Corti C, Modi S, Bardia A, Tolaney SM, et al. Antibody–drug conjugates: smart chemotherapy delivery across tumor histologies. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;72:165-182.

10. Drago JZ, Modi S, Chandarlapaty S. Unlocking the potential of antibody-drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2021;18:327-344.

11. Carter PJ, Senter PD. Antibody-drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Cancer J 2008;14:154-169.

12. Jen EY, Ko CW, Lee JE, Del Valle PL, Aydanian A, Jewell C, et al. FDA approval: gemtuzumab ozogamicin for the treatment of adults with newly diagnosed CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:3242-3246.

13. Dileo R, Mewawalla P, Babu K, Yin Y, Strouse C, Chen E, et al. A real-world experience of efficacy and safety of belantamab mafodotin in relapsed refractory multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J 2025;15:34.

14. Hungria V, Robak P, Hus M, Zherebtsova V, Ward C, Ho PJ, et al. DREAMM-7 investigators. Belantamab mafodotin, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2024;391:393-407.

15. Dimopoulos MA, Beksac M, Pour L, Delimpasi S, Vorobyev V, Quach H, et al. Belantamab mafodotin, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2024;391:408-421.

16. Aggarwal D, Yang J, Salam MA, Sengupta S, Al-Amin MY, Mustafa S, et al. Antibody-drug conjugates: the paradigm shifts in the targeted cancer therapy. Front Immunol 2023;14:1203073.

17. Hu Q, Wang L, Yang Y, Lee JB. Review of dose justifications for antibody-drug conjugate approvals from clinical pharmacology perspective: a focus on exposure-response analyses. J Pharm Sci 2024;113:3434-3446.

18. Sun S, Heske S, Mercadel M, Wimmer J. Predicting regulatory product approvals using a proposed quantitative version of FDA’s benefit–risk framework to calculate net-benefit score and benefit–risk ratio. Ther Innov Regul Sci 2021;55:129-137.

19. Hyogo A, Kaneko M, Narukawa M. Factors that influence FDA decisions for postmarketing requirements and commitments during review of oncology products. J Oncol Pract 2018;14:e34-e41.

20. Beck A, Haeuw JF, Wurch T, Goetsch L, Bailly C, Corvaïa N. The next generation of antibody-drug conjugates comes of age. Discov Med 2010;10:329-339.

21. Liu K, Li M, Li Y, Li Y, Chen Z, Tang Y, et al. A review of the clinical efficacy of FDA-approved antibody–drug conjugates in human cancers. Mol Cancer 2024;23:62.

22. Mahmood I. Clinical pharmacology of antibody-drug conjugates. Antibodies (Basel) 2021;10:20.

23. Kopp A, Hofsess S, Cardillo TM, Govindan SV, Donnell J, Thurber GM. Antibody–drug conjugate sacituzumab govitecan drives efficient tissue penetration and rapid intracellular drug release. Mol Cancer Ther 2023;22:102-111.

24. Su D, Zhang D. Linker design impacts antibody-drug conjugate pharmacokinetics and efficacy via modulating the stability and payload release efficiency. Front Pharmacol 2021;12:687926.