ICH E9(R1) 临床试验中的估计目标与敏感性分析(E9指导原则增补文件)

English Version

ICH E9(R1) Addendum: Statistical Principles for Clinical TrialsA.1. 目的和范围

为了给制药公司、监管机构、患者、医生和其他利益相关方的决策提供正确的信息,应明确描述特定医疗条件下治疗(药物)的获益和风险。如果不能对此进行明确描述,报告的“治疗效应”可能会被误解。本增补提出了一个结构化的框架,以加强参与制定临床试验目的、设计、实施、分析和解释的多学科间的交流,并加强申办方和监管机构之间关于临床试验中治疗效应的沟通。

构建相应临床问题的“估计目标”(见词汇表;A.3.)有助于精确描述治疗效应,这就需要深思熟虑地定义“伴发事件” (见词汇表;A.3.1.),如终止分配的治疗,使用额外或其他治疗,或终末事件(如死亡)等。估计目标的描述应该反映出与这些伴发事件相关的临床问题,并且本增补介绍了反映不同临床问题的策略。在描述临床问题时,策略的选择可能会影响到如何反映试验的更加常规的属性,例如治疗、人群或相关的变量(终点)。

临床试验数据的统计分析应当与估计目标对应。本增补阐明了“敏感性分析”(见词汇表)在探索主要统计分析结论稳健性中的作用。

本增补中,对原始ICH E9的引用采用x.y格式,对本增补的引用采用A.x.y.格式。

本增补就以下若干方面澄清和扩展了ICH E9。第一,ICH E9介绍了随机对照试验中对应于疗法策略的意向治疗(ITT)原则,据此对受试者进行随访、评估和分析,而不考虑其是否依从计划的治疗过程,这表明保持随机化为统计学检验提供了一个坚实的基础。ITT 原则具有以下三个含义。首先,试验分析应包括与研究问题相关的所有受试者。其次,受试者应按随机化时的分配纳入分析。最后,根据ITT原则(见ICH E9词汇表)的定义,无论是否依从预定的治疗过程,都应对受试者进行随访和评估,并在分析中使用这些评估。毫无疑问,随机化是对照临床试验的基石,分析时应最大限度地利用随机化的这一优势。然而,根据ITT 原则估计治疗效应能否总是代表与监管和临床决策最相关的治疗效应,这个问题仍然悬而未决。本增补中概述的框架为描述不同的治疗效应提供了基础,并提出了试验设计和分析需考虑的要点,以便估计治疗效应,为决策提供可靠依据。

第二,本增补重新审视了通常归为数据处理和“缺失数据”(见词汇表)的一些问题,并提出了两个重要的区别。首先,增补对终止随机分配的治疗和退出研究加以区分。前者代表一个伴发事件,需通过在试验目的中对估计目标的精确说明加以解决;后者导致缺失数据,需在统计分析中加以解决。例如,考虑在肿瘤学试验中转组治疗的受试者,以及由于试验完成而无法观测到结局事件的受试者。前者代表伴发事件,关于该事件的临床问题应明确。后者属于管理性删失,需要在统计分析中作为缺失数据问题加以解决。估计目标的清晰性为计划需要收集哪些数据提供了依据,以及哪些数据如果未被收集到即为缺失数据问题,需要在统计分析中加以解决。然后,可以选择解决缺失数据问题的方法,以与估计目标一致。其次,增补强调了不同伴发事件的不同影响。诸如终止治疗、转组治疗或使用额外药物等事件可能导致变量的后续观测值即使可以收集到数据也与估计目标不相关或难以解释。而对于死亡的受试者,死亡后的观测值是不存在的。

第三,在框架中考虑了与分析集概念相关的问题。第 5.2.节强烈建议优效性试验的分析基于全分析集,即尽可能包括所有随机化受试者的分析集。然而,试验往往包括对同一受试者的重复观测。某些受试者按计划收集的观测值可能被认为是无关的或难以解释的,剔除这些观测值,与从全分析集中完全剔除受试者可能具有类似的后果,即没有完全保留最初的随机化。这样做的一个后果是,随机化赋予关于治疗效应的检验假设的理论优势获益以及平衡基线混杂因素的实际获益可能被削弱。另外,有意义的结局变量取值可能不存在,例如当受试者已死亡。第 5.2.节没有直接阐明这些问题。这些问题要在考虑伴发事件的前提下,通过仔细定义关注的治疗效应来进行明确,既要确定要包括在治疗效应估计中的受试者人群,又要确定每个受试者包括在分析中的观测值。本增补也重新审视了使用符合方案集来分析的意义和作用,尤其是,是否需要用比分析符合方案集更能减少偏倚、更有可解读性的方式,来研究方案违背和偏离的影响。

最后,在敏感性分析部分进一步讨论了稳健性的概念(见1.2.)。特别区分了所选分析方法的假设的敏感性,以及分析方法选择上的敏感性。通过精确说明已达成共识的估计目标,以及与估计目标一致的分析方法且其预先设定的细节描述达到能使第三方精确地重现分析结果的程度,这样,监管机构对于一个特定分析可聚焦于假设偏离和数据局限的敏感性。

无论是基于有效性或安全性的治疗效应估计,还是对治疗效应相关假设的检验,本增补中概述的原则均适用。虽然主要关注的是随机临床试验,但这些原则也同样适用于单臂试验和观察性研究。该框架适用于任何数据类型,包括纵向数据、首次事件发作时间数据和复发事件数据。对于确证性临床试验和用于产生确证性结论的跨试验整合数据,监管部门对所述原则的应用将更为关注。

A.2. 将计划、设计、实施、分析和解释协调一致的框架

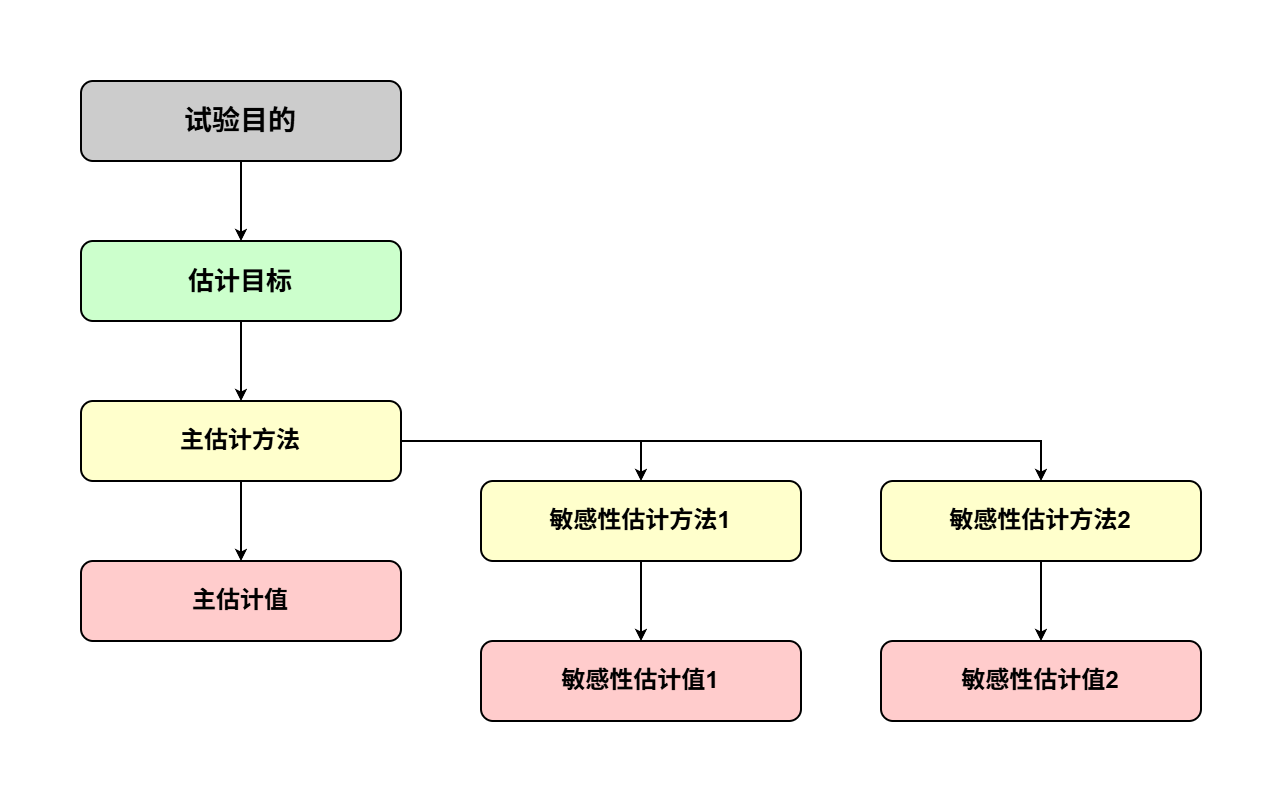

试验计划应按顺序进行(图 1)。应通过定义合适的估计目标,将明确的试验目的转化为关键的临床所关注的问题。估计目标根据特定的试验目的定义估计的目标(即“要估计什么”,见A.3.),然后可以选择合适的估计方法(即分析方法,称为主“估计方法”,见词汇表)(见 A.5.1.)。主估计方法将以特定假设为基础,为了探索根据主估计方法所作推断对偏离其基本假设的稳健性,应针对同一估计目标采用一种或多种形式进行敏感性分析(见A.5.2.)。

图1:协调估计的目标、估计的方法和敏感性分析,使其与给定试验目的对应

该框架有助于制定适当的试验计划,以明确区分估计的目标(试验目的,估计目标)、估计的方法(估计方法)、数值结果(“估计值”,见词汇表)和敏感性分析。这将有助于申办方的试验计划制定和监管机构的审评工作,并在双方讨论临床试验设计的适宜性和临床试验结果的解释时增强交流。

指定适当的估计目标(见 A.3.)通常是试验设计、实施(见A.4.)和分析(见A.5.)方面的主要决定因素。

A.3. 估计目标

药物开发和批准的核心问题是明确治疗效应是否存在,并估计其大小:如何比较相同受试者接受不同治疗的结局(即,如果受试者未接受治疗或接受不同治疗)。估计目标是对治疗效应的精确描述,反映了既定临床试验目的提出的临床问题。它在群体层面上总结了同一批患者在不同治疗条件下比较的结果。估计的目标将在临床试验之前定义。一旦定义了估计的目标,即可设计试验以可靠地估计治疗效应。

估计目标的描述涉及特定属性的精确说明,这些属性不仅应基于临床考虑而制定,还应基于所关注的临床问题中如何反映伴发事件。第 A.3.1.节介绍了伴发事件。第 A.3.2.节介绍了各种策略,来描述与伴发事件有关的问题。第 A.3.3.节描述了估计目标的属性,第 A.3.4.节则提出了估计目标构建的考虑要点。理解不同策略之间的差异,并精确阐明哪些策略用于构建估计目标,这一点至关重要。

A.3.1. 临床问题中反映的伴发事件

伴发事件是指治疗开始后发生的事件,可影响与临床问题相关的观测结果的解读或存在。在描述临床问题时,有必要阐明伴发事件,以便准确定义需要估计的治疗效应。

在描述治疗效应时需要考虑伴发事件,因为变量的观测结果可能受伴发事件的影响,而伴发事件的发生可能取决于治疗。例如,两名患者可能最初暴露于相同的治疗并提供相同的结局观测值,但如果其中一名患者接受了其他药物治疗,则两名患者之间,观测值所反映的治疗的信息会有所不同。此外,患者接受的治疗会影响到他们是否需要服用其他用药,以及是否可以继续接受治疗。与缺失数据不同,伴发事件不应被认为是临床试验中需要避免的缺陷。在临床试验中发生的终止既定治疗、使用其他药物和其他此类事件在临床实践中也可能发生,因此在定义临床问题时需要明确考虑这些事件发生的可能。

可影响观测结果解释的伴发事件包括终止所分配的治疗,和使用额外或其他治疗。使用额外或其他疗法可以有多种形式,包括改变基础治疗或合并治疗、转组治疗。影响观测结果存在的伴发事件包括终末事件,例如死亡和腿截肢(当评估糖尿病性足溃疡的症状时),而且这些事件不是变量本身的一部分。当某些临床事件的发生或不发生定义了一个主层时(见 A.3.2.),这些事件也可以是伴发事件。例如, 肿瘤领域中在评估缓解持续时间疗效时定义客观缓解的肿瘤缩小;对于初始未感染的接种疫苗受试者在评估感染严重程度疗效时的感染发生。

伴发事件可能仅由事件本身确定,如终止治疗,或可能有更详细的定义。详细的定义例如,可明确说明事件发生的原因,如因毒性作用终止治疗,或因缺乏疗效而终止治疗;事件可能需要达到一定量级或程度,如使用超过规定时间或剂量的其他药物;或明确说明事件发生的时机,可能与其对变量评估的接近程度有关。一些事件会无限期地影响结局观测值的解释,例如终止治疗,而另一些事件只会暂时影响,例如短期使用其他治疗。事实上,额外或其他治疗可以是多样的;可以是替代或补充受试者获益不足时的治疗,或作为对既定治疗不耐受的另一种选择,或作为控制疾病暂时急性发作的短期急性治疗。在临床试验中,额外或其他治疗通常是指诸如基础治疗、补救药物和禁用药物,要区分它们的不同作用以对其分别考虑。如果要使用不同的策略,则需要额外的详细信息,确定不同的伴发事件。例如,如果伴发事件不仅取决于未继续治疗,还取决于与未继续治疗相关的原因、程度或时机,则应在临床试验中准确定义和记录该附加信息。理论上,描述伴发事件可能体现治疗和随访非常具体的细节,例如长期治疗的单次漏服或日间服药的错误时间。如果预期这些具体标准不会影响对变量的解释,则不需要将它们作为伴发事件处理。

如上所述,在构建估计目标时需要考虑伴发事件。因为估计目标要在试验设计之前进行定义,所以无论是退出研究还是其他缺失数据的原因(例如生存结局的试验中的管理性删失)本身都不是伴发事件。退出试验的受试者在退出前可能已经发生了伴发事件。

A.3.2. Strategies for Addressing Intercurrent Events when Defining the Clinical Question of Interest

Descriptions of various strategies are listed below, each reflecting a different clinical question of interest in respect of a particular intercurrent event. Whether or not the naming convention is used, it is required that the choices of strategy are unambiguously clear once the estimand is constructed. It is not necessary to use the same strategy to address all intercurrent events. Indeed, different strategies will often be used to reflect the clinical question of interest in respect of different intercurrent events. Section A.3.4. gives some considerations on selecting strategies to construct an estimand.

Treatment policy strategy

The occurrence of the intercurrent event is considered irrelevant in defining the treatment effect of interest: the value for the variable of interest is used regardless of whether or not the intercurrent event occurs. For example, when specifying how to address use of additional medication as an intercurrent event, the values of the variable of interest are used whether or not the patient takes additional medication.

If applied in relation to whether or not a patient continues treatment, and whether or not a patient experiences changes in other treatments (e.g. background or concomitant treatments), the intercurrent event is considered to be part of the treatments being compared. In that case, this reflects the comparison described in the ICH E9 Glossary (under ITT Principle) as the effect of a treatment policy.

In general, the treatment policy strategy cannot be implemented for intercurrent events that are terminal events, since values for the variable after the intercurrent event do not exist. For example, an estimand based on this strategy cannot be constructed with respect to a variable that cannot be measured due to death.

Hypothetical strategies

A scenario is envisaged in which the intercurrent event would not occur: the value of the variable to reflect the clinical question of interest is the value which the variable would have taken in the hypothetical scenario defined.

A wide variety of hypothetical scenarios can be envisaged, but some scenarios are likely to be of more clinical or regulatory interest than others. For example, it may be of clinical or regulatory importance to consider the effect of a treatment under different conditions from those of the trial that can be carried out. Specifically, when additional medication must be made available for ethical reasons, a treatment effect of interest might concern the outcomes if the additional medication was not available. A very different hypothetical scenario might postulate that intercurrent events would not occur, or that different intercurrent events would occur. For example, for a subject that will suffer an adverse event and discontinue treatment, it might be considered whether the same subject would not have the adverse event or could continue treatment in spite of the adverse event. The clinical and regulatory interest of such hypotheticals is limited and would usually depend on a clear understanding of why and how the intercurrent event or its consequences would be expected to be different in clinical practice than in the clinical trial.

If a hypothetical strategy is proposed, it should be made clear what hypothetical scenario is envisaged. For example, wording such as “if the patient does not take additional medication” might lead to confusion as to whether the patient hypothetically does not take additional medication because it is not available or because the particular patient is supposed not to require it.

Composite variable strategies

This relates to the variable of interest (see A.3.3.). An intercurrent event is considered in itself to be informative about the patient’s outcome and is therefore incorporated into the definition of the variable. For example, a patient who discontinues treatment because of toxicity may be considered not to have been successfully treated. If the outcome variable was already success or failure, discontinuation of treatment for toxicity would simply be considered another mode of failure. Composite variable strategies do not need to be limited to dichotomous outcomes, however. For example, in a trial measuring physical functioning, a variable might be constructed using outcomes on a continuous scale, with subjects who die being attributed a value reflecting the lack of ability to function. Composite variable strategies can be viewed as implementing the intention-to-treat principle in some cases where the original measurement of the variable might not exist or might not be meaningful, but where the intercurrent event itself meaningfully describes the patient’s outcome, such as when the patient dies.

Terminal events, such as death, are perhaps the most salient examples of the need for the composite strategy. If a treatment saves lives, its effect on various measures in surviving patients may be of interest, but it would be inappropriate to say that the summary measure of interest was only the average value of some numerical measure in survivors. The outcome of interest is survival along with the numerical measures. For example, progression-free survival in oncology trials measures the treatment effect on a combination of the growth of the tumour and survival.

While on treatment strategies

For this strategy, response to treatment prior to the occurrence of the intercurrent event is of interest. Terminology for this strategy will depend on the intercurrent event of interest; e.g. “while alive”, when considering death as an intercurrent event.

If a variable is measured repeatedly, its values up to the time of the intercurrent event may be considered relevant for the clinical question, rather than the value at the same fixed timepoint for all subjects. The same applies to the occurrence of a binary outcome of interest up to the time of the intercurrent event. For example, subjects with a terminal illness may discontinue a purely symptomatic treatment because they die, yet the success of the treatment can be measured based on the effect on symptoms before death. Alternatively, subjects might discontinue treatment and, in some circumstances, it will be of interest to assess the risk of an adverse drug reaction while the patient is exposed to treatment.

Like the composite variable strategy, the while on treatment strategy can hence be thought of as impacting the definition of the variable, in this case by restricting the observation time of interest to the time before the intercurrent event. Particular care is required if the occurrence of the intercurrent event differs between the treatments being compared (see A.3.3.).

Principal stratum strategies

This relates to the population of interest (see A.3.3.). The target population might be taken to be the “principal stratum” (see Glossary) in which an intercurrent event would occur. Alternatively, the target population might be taken to be the principal stratum in which an intercurrent event would not occur. The clinical question of interest relates to the treatment effect only within the principal stratum. For example, it might be desired to know a treatment effect on severity of infections in the principal stratum of patients becoming infected after vaccination. Alternatively, a toxicity might prevent some patients from continuing the test treatment, but it would be desired to know the treatment effect among patients who are able to tolerate the test treatment.

It is important to distinguish “principal stratification” (see Glossary), which is based on potential intercurrent events (for example, subjects who would discontinue therapy if assigned to the test product), from subsetting based on actual intercurrent events (subjects who discontinue therapy on their assigned treatment). The subset of subjects who experience an intercurrent event on the test treatment will often be a different subset from those who experience the same intercurrent event on control. Treatment effects defined by comparing outcomes in these subsets confound the effects of the different treatments with the differences in outcomes possibly due to the differing characteristics of the subjects.

A.3.3. Estimand Attributes

The attributes below are used to construct the estimand, defining the treatment effect of interest.

The treatment condition of interest and, as appropriate, the alternative treatment condition to which comparison will be made (referred to as “treatment” through the remainder of this document). These might be individual interventions, combinations of interventions administered concurrently, e.g. as add-on to standard of care, or might consist of an overall regimen involving a complex sequence of interventions. (see Treatment Policy and Hypothetical strategies under A.3.2.).

The population of patients targeted by the clinical question. This will be represented by the entire trial population, a subgroup defined by a particular characteristic measured at baseline, or a principal stratum defined by the occurrence (or non-occurrence, depending on context) of a specific intercurrent event (see Principal Stratum strategies under A.3.2.).

The variable (or endpoint) to be obtained for each patient that is required to address the clinical question. The specification of the variable might include whether the patient experiences an intercurrent event (see Composite Variable and While on Treatment strategies under A.3.2.).

Precise specifications of treatment, population and variable are likely to address many of the intercurrent events considered in sponsor and regulator discussions of the clinical question of interest. The clinical question of interest in respect of any other intercurrent events will usually be reflected using the strategies introduced as treatment policy, hypothetical or while on treatment.

Finally, a population-level summary for the variable should be specified, providing a basis for comparison between treatment conditions.

When defining a treatment effect of interest, it is important to ensure that the definition identifies an effect due to treatment and not due to potential confounders such as differences in duration of observation or patient characteristics.

A.3.4. Considerations for Constructing an Estimand

The clinical questions of interest and associated estimands should be specified at the initial stages of planning any clinical trial. Precise specification of objectives for most trials will need to reflect discontinuation of treatment and use of additional or alternative treatments. In some settings terminal events, such as death, should be addressed. Some trial objectives can only be described with reference to clinical events, for example the duration of response in subjects who achieve a response.

The construction of an estimand should consider what is of clinical relevance for the particular treatment in the particular therapeutic setting. Considerations include the disease under study, the clinical context (e.g. the availability of alternative treatments), the administration of treatment (e.g. one-off dosing, short-term treatment or chronic dosing) and the goal of treatment (e.g. prevention, disease modification, symptom control). Also important is whether an estimate of the treatment effect can be derived that is reliable for decision making. For example, a clinical question on the treatment effect on clinical outcome regardless of which other therapies are to be used before that outcome is experienced differs to a clinical question on the treatment effect had no additional medication been available. Depending on the setting, either might represent a clinical question of interest. However, in both cases, a clinical trial designed to estimate these treatment effects will often include the possibility to use additional medications if medically required. For the former question, values after the use of additional treatment will be relevant. For the latter question, values after the additional treatment are not directly relevant since the values also reflect the impact of that additional medication. It should be agreed that reliable estimation is possible before the choice of estimand is finalised. This includes, for the latter question, the methods to replace observations that are not to be used in the analysis.

When constructing the estimand it is necessary to have a clear understanding of the treatment to which the clinical question of interest pertains (see A.3.3.). Clear specifications for the treatments of interest might already reflect multiple relevant intercurrent events. Specifically, a treatment might already reflect the clinical question of interest in respect of changes in background treatment, concomitant medications, use of additional or later-line therapies, treatment-switching and conditioning regimens. For example, it is possible to specify treatment as intervention A added to background therapy B, dosed as required. In that case, changes to the dose of background therapy B would not need to be considered as an intercurrent event. However, the use of an additional therapy would need to be considered as an intercurrent event. If use of any additional medication is also reflected, using the treatment policy strategy for example, then treatment might be specified as intervention A added to background therapy B, dosed as required, and with additional medication, as required. Alternatively, if the treatment is specified as intervention A, then both changes in background therapy and use of additional therapy would be addressed as intercurrent events.

Discussions should also consider whether specifications for the population and variable attributes should be used to reflect the clinical question of interest in respect of any intercurrent events. Strategies can then be considered for any other intercurrent events. Usually an iterative process will be necessary to reach an estimand that is of clinical relevance for decision making, and for which a reliable estimate can be made. Some estimands, in particular those for which the measurements taken are relevant to the clinical question, can often be robustly estimated making few assumptions. Other estimands may require methods of analysis with more specific assumptions that may be more difficult to justify and that may be more sensitive to plausible changes in those assumptions (see A.5.1.). Where significant issues exist to develop an appropriate trial design or to derive an adequately reliable estimate for a particular estimand, an alternative estimand, trial design and method of analysis would need to be considered.

Avoiding or over-simplifying the process of discussing and constructing an estimand risks misalignment between trial objectives, trial design, data collection and method of analysis. Whilst an inability to derive a reliable estimate might preclude certain choices of strategy, it is important to proceed sequentially from the trial objective and an understanding of the clinical question of interest, and not for the choice of data collection and method of analysis to determine the estimand.

The experimental situation should also be considered. If the management of subjects (e.g. dose adjustment for intolerance, rescue treatment for inadequate response, burden of clinical trial assessments) under a clinical trial protocol is justified to be different to that which is anticipated in clinical practice, this might be reflected in the construction of the estimand.

Once constructed, the estimand should define a target of estimation clearly and unambiguously. Consider an intercurrent event of discontinuation of treatment; it is of utmost importance to distinguish between treatment effects of interest based on the principal stratum of patients who would be able to continue if administered the test treatment and the effect during continued treatment. Furthermore, neither of these should be taken to represent an effect if all patients can continue with treatment.

As stated above, when using the hypothetical strategy, some conditions are likely to be more acceptable for regulatory decision making than others. The hypothetical conditions described should therefore be justified for the quantification of an interpretable treatment effect that is relevant to inform the decisions to be taken by regulators, and use of the medicine in clinical practice. The question of what the values for the variable of interest would have been if rescue medication had not been available may be an important one. In contrast, the question of what the values for the variable of interest would have been under the hypothetical condition that subjects who discontinued treatment because of adverse drug reaction had in fact continued with treatment, might not be justifiable as being of clinical or regulatory interest. A clinical question of interest based on the effect if all subjects had been able to continue with treatment is not well-defined without a thorough discussion of the hypothetical conditions under which it is supposed that they would have continued. The inability to tolerate a treatment may constitute, in itself, evidence of an inability to achieve a favourable outcome.

Characterising beneficial effects using estimands based on the treatment policy strategy might also be more generally acceptable to support regulatory decision making, specifically in settings where estimands based on alternative strategies might be considered of greater clinical interest, but main and sensitivity estimators cannot be identified that are agreed to support a reliable estimate or robust inference. An estimand based on the treatment policy strategy might offer the possibility to obtain a reliable estimate of a treatment effect that is still relevant. In this situation, it is recommended to also include those estimands that are considered to be of greater clinical relevance and to present the resulting estimates along with a discussion of the limitations, in terms of trial design or statistical analysis, for that specific approach. When constructing estimands based on the treatment policy strategy, inference can be complemented by defining an additional estimand and analysis pertaining to each intercurrent event for which the strategy is used; for example, contrasting both the treatment effect on a symptom score and the proportion of subjects using additional medication under each treatment. Similarly, an estimand using a while on treatment strategy should usually be accompanied by the additional information on the time to intercurrent event distributions, and an estimand based on a principal stratum would usefully be accompanied by information on the proportion of patients in that stratum, if available.

The considerations informing the construction of estimand to support regulatory decision making based on a non-inferiority or equivalence objective may differ to those for the choice of estimand for a superiority objective. As explained in ICH E9, the problem facing the regulator in their decision making is different when based on non-inferiority or equivalence studies compared to superiority studies. In Section 3.3.2. it is stated that such trials are not conservative in nature and the importance of minimising the number of protocol violations and deviations, non-adherence and study withdrawals is indicated. In Section 5.2.1. it is described that the result of the Full Analysis Set (FAS) is generally not conservative and that its role in such trials should be considered very seriously. Estimands that are constructed with one or more intercurrent events accounted for using the treatment policy strategy present similar issues for non-inferiority and equivalence trials as those related to analysis of the FAS under the ITT principle. Responses in both treatment groups can appear more similar following discontinuation of randomised treatment or use of another medication for reasons that are unrelated to the similarity of the initially randomised treatments. Estimands could be constructed to directly address those intercurrent events which can lead to the attenuation of differences between treatment arms (e.g. discontinuations from treatment and use of additional medications). When selecting strategies, it might be important to distinguish between trials designed to detect whether differences exist between treatments containing the same or similar active substance (e.g. comparison of a biosimilar to a reference treatment) and trials where a non-inferiority or equivalence hypothesis is used in order to establish and quantify evidence of efficacy. An estimand can be constructed to target a treatment effect that prioritises sensitivity to detect differences between treatments, if appropriate for regulatory decision making.

A.4. IMPACT ON TRIAL DESIGN AND CONDUCT

The design of a trial needs to be aligned to the estimands that reflect the trial objectives. A trial design that is suitable for one estimand might not be suitable for other estimands of potential importance. Clear definitions for the estimands on which quantification of treatments effects will be based should inform the choices that are made in relation to trial design. This includes determining the inclusion and exclusion criteria that identify the target population, the treatments, including the medications that are allowed and those that are prohibited in the protocol, and other aspects of patient management and data collection. If interest lies, for example, in understanding the treatment effect regardless of whether a particular intercurrent event occurs, a trial in which the variable is collected for all subjects is appropriate. Alternatively, if the estimands that are required to support regulatory decision making do not require the collection of the variable after an intercurrent event, then the benefits of collecting such data for other estimands should be weighed against any complications and potential drawbacks of the collection.

Efforts should be made to collect all data that are relevant to support estimation, including data that inform the characterisation, occurrence and timing of intercurrent events. Data cannot always be collected. Certainly, subjects cannot be retained in a trial against their will, and in some trials missing data for some subjects is inevitable by design, such as administrative censoring in trials with survival outcomes. On the contrary, the occurrence of intercurrent events such as discontinuation of treatment, treatment switching, or use of additional medication, does not imply that the variable cannot be measured thereafter, though the measures may not be relevant. For terminal events such as death, the variable cannot be measured after the intercurrent event, but neither should these data generally be regarded as missing.

Not collecting any data needed to assess an estimand results in a missing data problem for subsequent statistical inference. The validity of statistical analyses may rest upon untestable assumptions and, depending on the proportion of missing data, this may undermine the robustness of the results (see A.5.). A prospective plan to collect informative reasons for why data intended for collection are missing may help to distinguish the occurrence of intercurrent events from missing data. This in turn may improve the analysis and may also lead to a more appropriate choice of sensitivity analysis. For example, “loss to follow-up” may more accurately be recorded as “treatment discontinuation due to lack of efficacy”. Where that has been defined as an intercurrent event, this can be reflected through the strategy chosen to account for that intercurrent event and not as a missing data problem. To reduce missing data, measures can be implemented to retain subjects in the trial. However, measures to reduce or avoid intercurrent events that would normally occur in clinical practice risk reducing the external validity of the trial. For example, selection of the trial population or use of titration schemes or concomitant medications to mitigate the impact of toxicity might not be suitable if those same measures would not be implemented in clinical practice.

Randomisation and blinding remain cornerstones of controlled clinical trials. Design techniques for avoiding bias are addressed in Section 2.3. Certain estimands may necessitate, or may benefit from, use of trial designs such as run-in or enrichment designs, randomised withdrawal designs, or titration designs. It might be of interest to identify the principal stratum of subjects who can tolerate a treatment using a run-in period, in advance of randomising those subjects between test treatment and control. Dialogue between regulator and sponsor would need to consider whether the proposed run-in period is appropriate to identify the target population, and whether the choices made for the subsequent trial design (e.g. washout period, randomisation) supports the estimation of the target treatment effect and associated inference. These considerations might limit the use of these trial designs, and use of that particular strategy.

A precise description of the treatment effects of interest should inform sample size calculations. Particular care should be taken when making reference to historical studies that might, implicitly or explicitly, have reported estimated treatment effects or variability based on a different estimand. Where all subjects contribute information to the analysis, and where the impact of the strategy to reflect intercurrent events is included in the effect size that is targeted and the expected variance, it is not usually necessary to additionally inflate the calculated sample size by the expected proportion of subject withdrawals from the trial.

Section 7.2. addresses issues related to summarising data across clinical trials. The need to have consistent definitions for the variables of interest is highlighted and this can be extended to the construction of estimands. Hence, in situations when synthesising evidence from across a clinical trial programme is envisaged at the planning stage, a suitable estimand should be constructed, included in the trial protocols, and reflected in the choices made for the design of the contributing trials. Similar considerations apply to the design of a meta-analysis, using estimated effect sizes from completed trials to determine non-inferiority margins, or the use of external control groups for the interpretation of single-arm trials. A naïve comparison between data sources, or integration of data from multiple trials without consideration and specification of the estimand that is addressed in each data presentation or statistical analysis, could be misleading.

More generally, a trial is likely to have multiple objectives translated into multiple estimands, each associated with statistical testing and estimation. The multiplicity issues arising should be addressed.

A.5. IMPACT ON TRIAL ANALYSIS

A.5.1. Main Estimation

An estimand for the effect of treatment relative to a control will be estimated by comparing the outcomes in a group of subjects on the treatment to those in a similar group of subjects on the control. For a given estimand, an aligned method of analysis, or estimator, should be implemented that is able to provide an estimate on which reliable interpretation can be based. The method of analysis will also support calculation of confidence intervals and tests for statistical significance. An important consideration for whether an interpretable estimate will be available is the extent of assumptions that need to be made in the analysis. Key assumptions should be stated explicitly together with the estimand and accompanying main and sensitivity estimators. Assumptions should be justifiable and implausible assumptions should be avoided. The robustness of the results to potential departures from the underlying assumptions should be assessed through an estimand-aligned sensitivity analysis (see A.5.2.). Estimation that relies on many or strong assumptions requires more extensive sensitivity analysis. Where the impact of deviations from assumptions cannot be comprehensively investigated through sensitivity analysis, that particular combination of estimand and method of analysis might not be acceptable for decision making.

All methods of analysis rely on assumptions, and different methods may rely on different assumptions even when aligned to the same estimand. Nevertheless, some kinds of assumption are inherent in all methods of analysis aligned to estimands that use each of the different strategies outlined; for example, the methodology for predicting the outcomes that would have been observed in the hypothetical scenario, or for identifying a suitable target population in a principal stratum strategy. Some examples are given below related to the different strategies used to reflect the occurrence of intercurrent events. The issues highlighted will be key components of discussion between sponsor and regulator in advance of an estimand, main analysis and sensitivity analysis being agreed.

Analysis aligned with a treatment policy strategy to address a given intercurrent event may entail stronger or weaker assumptions depending on the design and conduct of the trial. When most subjects are followed-up even after the respective intercurrent event (e.g. discontinuation of treatment), the remaining problem of missing data may be relatively minor. In contrast, when observation is terminated after an intercurrent event, which is obviously undesirable in respect of this strategy, the assumption that (unobserved) outcomes for discontinuing subjects are similar to the (observed) outcomes for those who remain on treatment will often be implausible. An alternative approach to handle the missing data would need to be justified and sensitivity analysis will be expected.

Analysis aligned to a hypothetical strategy involves outcomes different from those actually observed; for example, outcomes if rescue medication had not been given when in fact it was. Observations before the rescue medication and observations on subjects who did not require rescue medication may be informative, but only under strong assumptions.

A composite variable strategy can avoid statistical assumptions about data after an intercurrent event by considering occurrence of the intercurrent event as a component of the outcome. The potential concern relates less to assumptions for estimation, and more to the interpretation of the estimated treatment effect. For the estimand to be interpretable, if scores are assigned for failure because the intercurrent event occurs, these should meaningfully reflect the lack of benefit to the patient (e.g. death may be reflected differently than discontinuation of treatment due to adverse event).

Estimands constructed based on a while on treatment strategy can be estimated provided outcomes are collected up to the time of the intercurrent event. Again, the crucial assumptions concern interpretation. Take discontinuation of treatment by way of example. Outcomes while on treatment may be improved but the treatment may also shorten, or lengthen, the treatment period by provoking, or delaying, discontinuations, and both these effects should be considered in interpretation and assessment of clinical benefit.

Analysis aligned to a principal stratum strategy usually requires strong assumptions. For example, some principal stratification methods infer this from baseline characteristics of the subjects, but the correctness of this inference may be difficult to assess. This difficulty cannot be avoided by simplified methods, however. For example, simply comparing subjects who do not have an intercurrent event on the test treatment to those who do not have an event on control, assuming intercurrent events are unrelated to treatment, is very difficult to justify.

Even after defining estimands that address intercurrent events in an appropriate manner and making efforts to collect the data required for estimation (see A.4.), some data may still be missing, including e.g. administrative censoring in trials with survival outcomes. Failure to collect relevant data should not be confused with the choice not to collect, or to collect and not to use, data made irrelevant by an intercurrent event. For example, data that were intended to be collected after discontinuation of trial medication to inform an estimand based on the treatment policy strategy are missing if uncollected; however, the same data points might be irrelevant for another strategy, and thus, for the purpose of that second estimand, are not missing if uncollected. Where those efforts to collect data are not successful it becomes necessary to make assumptions to handle the missing data in the statistical analysis. Handling of missing data should be based on clinically plausible assumptions and, where possible, guided by the strategies employed in the description of the estimand. The approach taken may be based on observed covariates and post-baseline data from individual subjects and from other similar subjects. Criteria to identify similar subjects might include whether or not the intercurrent event has occurred. For example, for subjects who discontinue treatment without further data being collected, a model may use data from other subjects who discontinued treatment but for whom data collection has continued.

A.5.2. Sensitivity Analysis

A.5.2.1. Role of Sensitivity Analysis

Inferences based on a particular estimand should be robust to limitations in the data and deviations from the assumptions used in the statistical model for the main estimator. This robustness is evaluated through a sensitivity analysis. Sensitivity analysis should be planned for the main estimators of all estimands that will be important for regulatory decision making and labelling in the product information. This can be a topic for discussion and agreement between sponsor and regulator.

The statistical assumptions that underpin the main estimator should be documented. One or more analyses, focused on the same estimand, should then be pre-specified to investigate these assumptions with the objective of verifying whether or not the estimate derived from the main estimator is robust to departures from its assumptions. This might be characterised as the extent of departures from assumptions that change the interpretation of the results in terms of their statistical or clinical significance (e.g. tipping point analysis).

Distinct from sensitivity analysis, where investigations are conducted with the intent of exploring robustness of departures from assumptions, other analyses that are conducted in order to more fully investigate and understand the trial data can be termed “supplementary analysis” (see Glossary; A.5.3.). Where the primary estimand(s) of interest is agreed between sponsor and regulator, the main estimator is pre-specified unambiguously, and the sensitivity analysis verifies that the estimate derived is reliable for interpretation, supplementary analyses should generally be given lower priority in assessment.

A.5.2.2. Choice of Sensitivity Analysis

When planning and conducting a sensitivity analysis, altering multiple aspects of the main analysis simultaneously can make it challenging to identify which assumptions, if any, are responsible for any potential differences seen. It is therefore desirable to adopt a structured approach, specifying the changes in assumptions that underlie the alternative analyses, rather than simply comparing the results of different analyses based on different sets of assumptions. The need for analyses varying multiple assumptions simultaneously should then be considered on a case by case basis. A distinction between testable and untestable assumptions may be useful when assessing the interpretation and relevance of different analyses.

The need for sensitivity analysis in respect of missing data is established and retains its importance in this framework. Missing data should be defined and considered in respect of a particular estimand (see A.4.). The distinction between data that are missing in respect of a specific estimand and data that are not directly relevant to a specific estimand gives rise to separate sets of assumptions to be examined in sensitivity analysis.

A.5.3. Supplementary Analysis

Interpretation of trial results should focus on the main estimator for each agreed estimand providing that the corresponding estimate is verified to be robust through the sensitivity analysis. Supplementary analyses for an estimand can be conducted in addition to the main and sensitivity analysis to provide additional insights into the understanding of the treatment effect. They generally play a lesser role for interpretation of trial results. The need for, and utility of, supplementary analyses should be considered for each trial.

Section 5.2.3. indicates that it is usually appropriate to plan for analyses based on both the FAS and the Per Protocol Set (PPS) so that differences between them can be the subject of explicit discussion and interpretation. Consistent results from analyses based on the FAS and the PPS is indicated as increasing confidence in the trial results. It is also described in Section 5.2.2. that results based on a PPS might be subject to severe bias. In respect of the framework presented in this addendum, it may not be possible to construct a relevant estimand to which analysis of the PPS is aligned. As noted above, analysis of the PPS does not achieve the goal of estimating the effect in any principal stratum, for example, in those subjects able to tolerate and continue to take the test treatment, because it may not compare similar subjects on different treatments.

Protocol violations and deviations might exclude subjects from the PPS, for example by having a visit outside a time window, without an intercurrent event necessarily having occurred. Likewise, subjects could experience an intercurrent event, such as death, without having deviated from the protocol. Notwithstanding the differences between violations and deviations from the protocol and intercurrent events, events likely to affect the interpretation or existence of measurements are considered in the description of the estimand. Estimands might be constructed, with aligned method of analysis, that better address the objective usually associated with the analysis of the PPS. If so, analysis of the PPS might not add additional insights.

A.6. DOCUMENTING ESTIMANDS AND SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS

A trial protocol should define and specify explicitly a primary estimand that corresponds to the primary trial objective. The protocol and the analysis plan should pre-specify the main estimator that is aligned with the primary estimand and leads to the primary analysis, together with a suitable sensitivity analysis to explore the robustness under deviations from its assumptions. Estimands for secondary trial objectives (e.g. related to secondary variables) that are likely to support regulatory decisions should also be defined and specified explicitly, each with a corresponding main estimator and a suitable sensitivity analysis. Additional exploratory trial objectives may be considered for exploratory purposes, leading to additional estimands.

The choice of the primary estimand will usually be the main determinant for aspects of trial design, conduct and analysis. Following usual practices, these aspects should be well documented in the trial protocol. If secondary estimands are of key interest, these considerations may be extended to support these as needed and should be documented as well. Beyond these aspects, the conventional considerations for trial design, conduct and analysis remain the same.

While it is to the benefit of the sponsor to have clarity on what is being estimated, it is not a regulatory requirement to document an estimand for each exploratory objective.

Results from the main, sensitivity and supplementary analyses should be reported systematically in the clinical trial report, specifying whether each analysis was pre-specified, introduced while the trial was still blinded, or performed post hoc. Summaries of the number and timings of each intercurrent event in each treatment group should be reported.

Changes to the estimand during the trial can be problematic and can reduce the credibility of the trial. Addressing intercurrent events that were not foreseen at the design stage, and are identified during the conduct of the trial, should discuss not only the choices made for the analysis, but the effect on the estimand, i.e. on the description of the treatment effect that is being estimated, and the interpretation of the trial results. A change to the estimand should usually be reflected through amendment to the protocol.

GLOSSARY

| Term | Content |

|---|---|

| Estimand: | A precise description of the treatment effect reflecting the clinical question posed by the trial objective. It summarises at a population-level what the outcomes would be in the same patients under different treatment conditions being compared. |

| Estimate: | A numerical value computed by an estimator. |

| Estimator: | A method of analysis to compute an estimate of the estimand using clinical trial data. |

| Intercurrent Events: | Events occurring after treatment initiation that affect either the interpretation or the existence of the measurements associated with the clinical question of interest. It is necessary to address intercurrent events when describing the clinical question of interest in order to precisely define the treatment effect that is to be estimated. |

| Missing Data: | Data that would be meaningful for the analysis of a given estimand but were not collected. They should be distinguished from data that do not exist or data that are not considered meaningful because of an intercurrent event. |

| Principal Stratification: | Classification of subjects according to the potential occurrence of an intercurrent event on all treatments. With two treatments, there are four principal strata with respect to a given intercurrent event: subjects who would not experience the event on either treatment, subjects who would experience the event on treatment A but not B, subjects who would experience the event on treatment B but not A, and subjects who would experience the event on both treatments. In this document a principal stratum refers to any of the strata (or combination of strata) defined by principal stratification. |

| Sensitivity Analysis: | A series of analyses conducted with the intent to explore the robustness of inferences from the main estimator to deviations from its underlying modelling assumptions and limitations in the data. |

| Supplementary Analysis: | A general description for analyses that are conducted in addition to the main and sensitivity analysis with the intent to provide additional insights into the understanding of the treatment effect. |